Eviction of Dutch Jews from Nazi-ravaged synagogue brings back bitter memories

Published August 2, 2018

The scroll’s introduction in 2014 was an important moment for the Beth Shoshana Masorti community that Furstenberg helped establish in 2010 in this city of nearly 100,000 residents located 60 miles east of the capital Amsterdam.

After all, it was proof that Jewish life had finally returned to a place where it had been uprooted and destroyed.

“I felt that this was it, nothing could reverse our presence as part of this city,” Furstenberg, a 49-year-old teacher and chairman of Deventer’s Jewish community, told JTA on Monday.

Furstenberg had been overly optimistic.

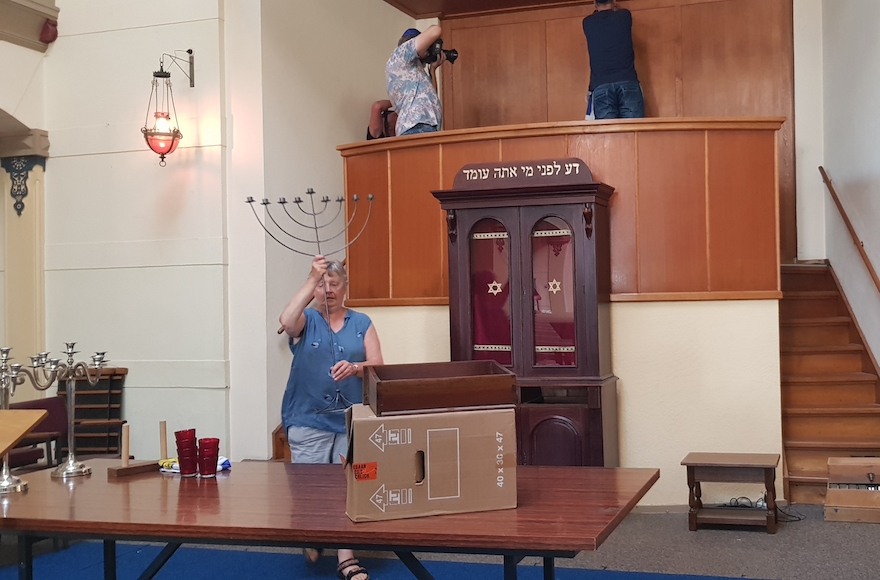

On Monday, he and a dozen other members of their congregation of 35 had to take away the scroll and all the other ritual possessions and load them into a white van.

The building housing the Great Synagogue of Deventer was sold in January by the church that had owned it for decades. The developers, a Dutch-Turkish restaurant owner and his associate, then evicted the congregants amid a legal fight over the owners’ plan to turn the place into an eatery.

For Deventer, the eviction meant “the end of a Jewish presence in this city,” Sanne Terlouw, a founding member of Beth Shoshana and a renowned author, told JTA with tears in her eyes on the day of the move.

But for many other Dutch Jews, the demise of the Great Synagogue of Deventer signals a broader demographic shift: Jewish life and heritage are becoming increasingly difficult to maintain outside Amsterdam, where most Dutch Jews live, because of secularization and the echoing losses of the Holocaust.

“Of course it’s sad, we’re losing a piece of our history,” said Esther Voet, editor in chief of the NIW Jewish weekly in Amsterdam. “But the reality is that this small Jewish community cannot afford to stay in that huge synagogue. That’s just the way it is.”

With no synagogue of its own, Beth Shoshana will move to the nearby municipality of Raalte, where it will share space with an existing congregation. Voet says she finds this “a reasonable solution” born out of a “regrettable reality.”

But in Deventer and beyond, the evicted congregants appeared less resigned to the change than Voet.

On Monday, the congregation gathered one last time for a snack in the building they had just emptied of its possessions. Sipping black coffee and eating prune cake, they sang in passionate Hebrew “Am Yisrael Chai” and “Kol Ha’Olam Kulo” — “The People of Israel Live” and “The World is a Narrow Bridge.” Some of the congregants cried; others tried to console them.

‘This was our home for a long period,” Ehud Posthumos, 79, a retired Royal Netherlands Air Force officer, told JTA. “On winter nights, we’d gather here in the cold – we never heated the place properly to save on utilities – and although outside it turned very dark early in the afternoon, here inside we had a great source of light. And now it feels like losing a home.”

A congregant helps pack up the synagogue’s belongings, July 30, 2018. (Cnaan Liphshiz)

Maurice Swirc, the former editor in chief of NIW, called the synagogue’s sale “a scandal” and found it “very painful.” Dutch authorities, he said, “were partially responsible for the fact that Deventer does not have enough Jews to maintain she synagogue. The least they could do is help preserve it.”

The affair prompted intense interest internationally. JTA’s video report of the community leaving the shul has been viewed more than 200,000 times on Facebook.

Ronny Naftaniel, a founder of The Hague Jewish Heritage group, said the synagogue’s sale is unusual “for a city such as Deventer, where authorities have a high awareness for heritage.” Deventer, where wealthy Jewish cattle dealers left an indelible mark and where a part of Naftaniel’s family lived before the Holocaust, “could have set aside this space,” he said.

Until recently, Furstenberg’s community was able to hold on to its synagogue thanks to the Christian Reformed Churches group. It bought the building in 1951 from the severely depleted Jewish community of Deventer and turned the structure into a church, complete with a massive pipe organ that the group installed.

In 2010, Furstenberg and other Jews from the area began convening at a nearby Jewish club and asked the church’s permission to re-establish a synagogue in the hall, which they began renting from the church at a subsidized rate. But the church had to sell the building this year. The highest bidder was Ayhan Sahin, the Dutch-Turkish developer, and his associate, Carlus Lenferink.

This summer, the entrepreneurs announced their plan to turn the synagogue into a restaurant. Furstenberg objected and the city declined to approve the plan.

Amid negotiations with the Jewish community, Sahin was quoted as saying: “If need be, I’ll turn it into a mosque,” according to De Stentor regional daily. He later said he would allow the Jewish community to stay, “but only if they pay full rent” – an unlikely prospect for the small congregation, which has no sources of income and could barely afford maintenance fees when it rented the shul at a subsidized price from the church.

Maarten-Jan Stuurman, a spokesman for the Deventer municipality, told De Stentor that the city tried to help the Jewish community stay, but ultimately “it is not the city’s task to buy religious properties it does not use.” The issue of rent, eh said, “is at the discretion of the owner.”

Losing the synagogue is “a failure and a major step back for the city,” Furstenberg said, his voice echoing in the tall and now empty space where his congregation would gather once every three weeks and on Jewish holidays. “Once again, the city is looking on as its synagogue is being destroyed.”

Furstenberg’s j’accuse, spoken in Dutch in the presence of local reporters, was a reference to the unusual and painful wartime history of the building. Unlike most Dutch synagogues, the one in Deventer was not confiscated in the orderly and methodical Nazi manner. Instead it was ransacked by a rabble belonging to the Dutch Nazi party, NSB, on July 25, 1941.

Congregants contemplate the end of the Great Synagogue of Deventer in its current home, July 30, 2018. (Cnaan Liphshiz)

Under the gaze of local police officers, they smashed the furniture, hacked open the Torah ark, tore up the scroll, pulled down the chandeliers and dislodged the bimah of the building, which was built in 1892.

But that violence paled in comparison to the deportations of the congregants the next summer. Of the 590 people registered as Jews in Deventer in 1942, the Nazis murdered 401. It was a typical statistic in a country where the Nazis and local collaborators were responsible for killing at least 75 percent of Jews – the highest death rate in Nazi-occupied Western Europe.

Dutch Jewry, which numbered 140,000 before the Holocaust, never came close to replenishing its numbers. Today, Holland has about 45,000 Jews, according to the European Jewish Congress.

The Deventer synagogue played a role in the survival of at least two Jews.

Simon van Spiegel, his brother, Bubi, and Meier de Leeuw hid in the building’s attic for a while. Bubi was caught by the Germans after they received an anonymous tip. His brother and de Leeuw escaped. Simon’s daughter, Liesje Tesler-Van Spiegel, who lives in Israel, visited her father’s hiding place for the first time last month.

“I remember all of them,” Roelof de Vries, 86, a carpenter whose family worked as caretakers at the synagogue before the Holocaust.

“Even if this place becomes a restaurant, I’ll never forget my friend Bubi, whom they gassed along with so many others,” he said, weeping.

Referring to the genocide, Furstenberg said “This is the reason there are not enough Jews to afford this place.”

In the cool interior of the Great Synagogue – a tall building in the neo-Moorish style – he added: “This is not just a story about a dwindling faith community, like all those churches that get turned into a discotheques. This is an aftereffect of the Holocaust.”