Battling Zika, Brazil’s Jews turn to bug repellent and indoor activities

Published March 7, 2016

A lab technician handling the mosquito that causes the Zika virus at a research facility in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Feb. 19, 2016. (Dado Galdieri/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

RIO DE JANEIRO (JTA) – Despite recent summer temperatures here topping out at 42 degrees Celsius (109 Fahrenheit), Milena Rozenbrah has become accustomed recently to dressing in pants and long sleeves when she leaves home.

ADVERTISEMENT

A Jewish mother in Brazil’s second-largest city, Rozenbrah is concerned not for the religious value of tzniut, or modesty, but for Aedes aegypti, the mosquito that transmits the feared Zika virus and which has become one of Brazil’s national enemies.

Brazilians have been in a state of panic over Zika, which is believed to cause birth defects and other medical problems, and Brazil’s 120,000-member Jewish community is hardly immune. Rozenbrah persuaded other mothers at her son’s Jewish day school to buy a gallon of the best mosquito repellent on the market and have the teacher apply a generous layer twice a day.

“We have crossed out of our family routine going to the Botanical Gardens and all green areas,” Rozenbrah told JTA. “We have anti-mosquito scented vaporizers all over our house and we avoid going out early in the morning or late in the afternoon, the most dangerous periods with more mosquitoes. Also, we keep the air conditioners on almost 24/7, which has made our electricity bill skyrocket.”

Brazil is ground zero for the growing Zika crisis. Last month, the World Health Organization declared Zika a global health threat out of concern that it is likely responsible for a spike in Brazilian cases of microcephaly, a condition in which babies are born with small heads and permanent brain damage. The risks to children and adults are less clear, but symptoms can include fever, rash, joint pain, muscle pain and headaches. There is no vaccine or specific treatment, according to Brazil’s Ministry of Health.

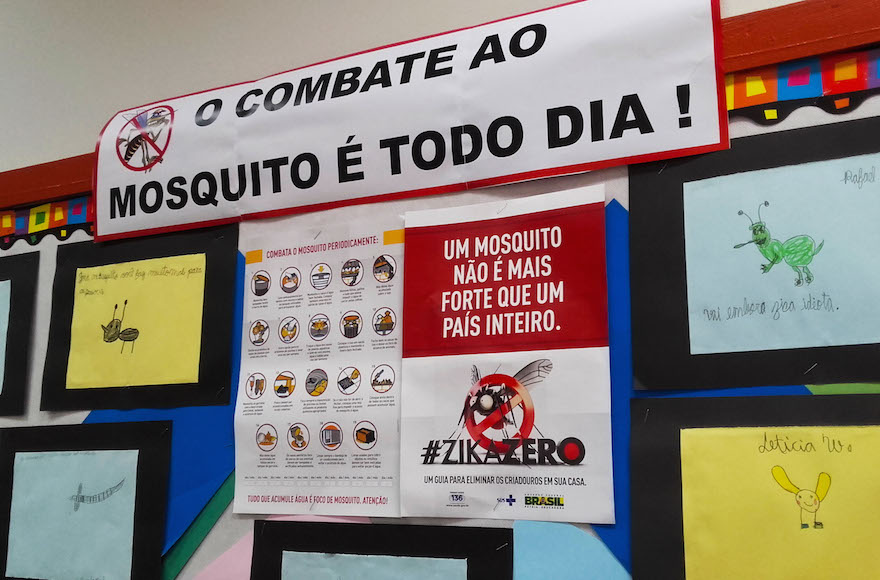

At Brazil’s largest Jewish school, the Liessin school, students are participating in the Zika Zero campaign. (Marcus Moraes)

ADVERTISEMENT

Though the worst-hit areas of Brazil are in the country’s Northeast, Rio, home to approximately one-third of Brazil’s Jews, has also felt the effects. The city is the site of the enormous Tijuca Forest and other natural landscapes that provide vast habitats for the aegypti mosquitoes. During the Carnival holidays last month, some Jewish families gave up their traditional excursions to the mountain refuge of Teresopolis, where the Zika threat is thought to be greater, preferring to stay in Rio, which has better medical resources.

At Rozenbrah’s son’s school, Liessin, the largest Jewish day school in Brazil with some 1,500 students, there have been no reported absences due to Zika, dengue or chikungunya, the other viruses associated with the Aedes mosquito. Pedagogic coordinator Maria do Carmo Iff believes prevention has been key.

“Our strategies include campaigns, training, latest news on bulletin boards, leaflets produced by the students, chat circles, drama, games, videos and much more,” Iff told JTA. “The whole school community must be involved, but mainly the children and teenagers, who are the best multipliers of our Zika Zero campaign. We also ask parents to keep in touch with us about any symptom that may appear.”

Erica Saubermann Alem, a mother of two who lives across the street from Liessin, is skeptical about the prevention approach. Ten years after she had dengue fever, another mosquito-borne illness that can cause Zika-like symptoms, she came down with Zika last month and wound up in the emergency room with rashes on her skin, severe headache and acute joint pain.

“In my opinion, repellents are a waste of time,” Alem said. “They are poisonous, kids don’t like it and their effect doesn’t last long. And protection is not 100 percent.”

Another Liessin mother, Juliana Eidelman, is eight months pregnant. Despite the prevention campaign, she says she has never been so frightened – even more so than when she was expecting her first child in the midst of the global swine flu epidemic in 2010.

“If I could have known in advance, I would have put off my current pregnancy,” Eidelman said. “Microcephaly is a very real risk. Now that my baby is formed, I am a bit calmer. But I still apply repellent along with makeup several times a day.”

Milena Rozenbrah and her family. (Courtesy of Rozenbrah family)

The link between microcephaly and Zika is a matter of some dispute, and doctors have been offering conflicting advice. One of the most prominent obstetricians in the Rio Jewish community, Janine Cynamon, who is also an infertility specialist, has been advising her older patients not to wait to get pregnant. But for younger patients, she recommends delaying pregnancy or freezing embryos until a vaccine for Zika is available.

“Our religion does not forbid contraception,” Cynamon said. “Therefore, I have been advising young hopeful mothers not to get pregnant before April [when the risk of mosquito transmission is highest].”

Cynamon sees patients at her office in Copacabana, one of this city’s main Jewish neighborhoods and home to several synagogues and Jewish institutions. In neighboring Ipanema, Dr. Betty Moszkowicz, a pediatrician, is less convinced that Zika poses a risk to the unborn.

“I don’t recommend postponing pregnancy,” Moszkowicz said. “The association between Zika and microcephaly is still very controversial and I am personally not convinced.”

The Health Ministry has yet to establish a firm link between Zika and birth defects, though several recent studies have found evidence of a connection. The ministry does recommend pregnant women use insect repellent, and the World Health Organization says avoiding mosquito bites is the best prevention.

Indeed, the need to control Zika has even led one Rio rabbi to assert that the need to prevent the disease’s spread overrides religious prohibitions against killing bugs on the Sabbath.

“Mothers must take all measures against Zika, such as applying repellent,” said Rabbi Yehoshua Goldman, the chief Chabad envoy in Rio. “The mosquito can be killed even on Shabbat, for it threatens life.”