At this Holocaust museum, you can speak with holograms of survivors

Published January 22, 2018

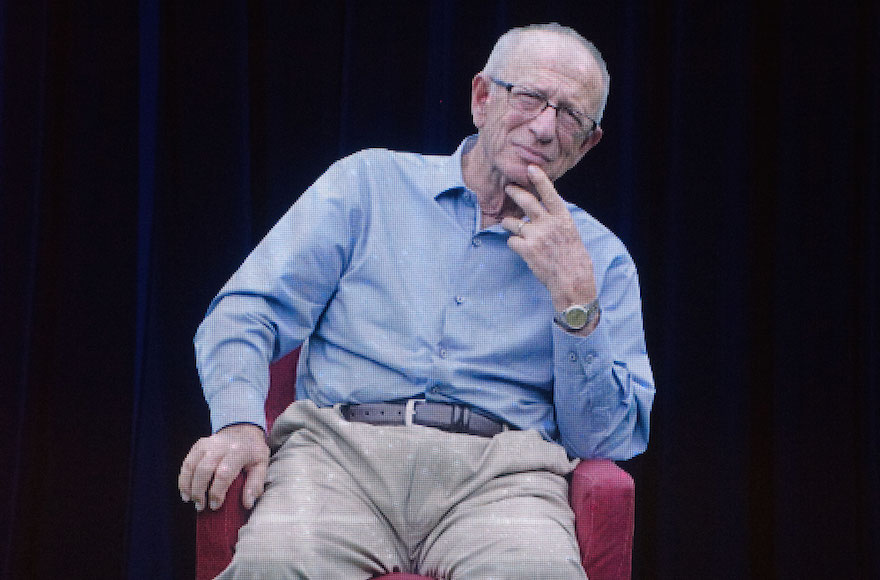

A holographic image of Holocaust survivor Sam Harris Kildeer on display at the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center in Skokie, Ill. (Ron Gould)

SKOKIE, Ill. (JTA) — In an otherwise darkened theater, viewers gasped when they saw what appeared to be a seated 83-year-old man wearing a light green button-down shirt and khaki pants.

ADVERTISEMENT

Aaron Elster of Chicago seemed to be answering questions about his unbelievable escape from the Sokolov ghetto in Poland as a 10-year-old. Elster was forced to hide in a dark, filthy attic for two years during World War II.

“Why didn’t your sisters run away with you [from the ghetto]?” asked Suri Johnson, 11, of Wisconsin. A docent repeated the question into a microphone.

“It was an impossibility,” Elster responded. “There were hundreds of people guarded by Ukrainian soldiers with rifles … There was no way they could have run. I crawled behind the people on my stomach. They didn’t see me.”

The testimony was remarkable, moving. But Elster wasn’t in the room. Instead the audience was interacting with a holographic image of the Holocaust survivor that was created two years before.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center, located in this suburb about 15 miles north of Chicago, is the first to permanently showcase the New Dimensions in Testimony oral history project, which has created holographic images from extensive interviews of 15 Holocaust survivors. The images of the seven survivors from Chicago are shown on rotation at the center.

The images are produced by the University of Southern California’s Institute for Creative Technologies, along with the USC Shoah Foundation — a nonprofit that famed director Steven Spielberg founded in 1994 to preserve Holocaust and other genocide survivor testimonies. The museum’s new $5 million center, titled Take A Stand, opened in October.

(The images currently on display are technically not true holograms — they are the product of two-dimensional technology and the Pepper’s ghost illusion technique — but are still vivid.)

Aaron Elster filming on a set in Los Angeles. (Ron Gould)

At the Illinois museum, visitors can find the holographic displays in a theater dedicated to the exhibit. Before any conversation happens, viewers are shown a five-minute introductory video narrated by the featured survivor. After the video, which tells the survivor’s individual story, the image leans forward and says, “But I have so much more to tell you. Now I’d like you to ask me questions.” Then it switches to interactive mode.

The hologram of each survivor can conceivably answer thousands of questions. Much like Apple’s Siri technology, the voice-recognition system responds to audience questions by picking up on key words.

After asking her question, Suri Johnson told JTA that she found the experience very “cool,” partly because she had no idea how it worked.

“It enables the most life-like conversational opportunity that you can possibly imagine,” said the museum’s CEO, Susan Abrams.

Aaron Elster stands in front of his hologram. (Ron Gould)

The project was envisioned by Heather Maio, the managing director of Conscience Display, which specializes in exhibition design and interactive storytelling. Her company typically creates realistic combat scenes, complete with visuals and dialogue, for military personnel to drill with.

Maio, who is married to Stephen Smith, executive director of the USC Shoah Foundation, thought an exhibit that allowed people to casually walk up to Holocaust survivors and ask them questions could create a powerful experience.

“This kind of visual imagery and interactivity will be the norm for the next generation, and that’s what we’re preparing for,” Smith said.

The project took a toll on Elster, an insurance agency owner who has lived in Chicago since 1947. He had to fly to Los Angeles two years ago for a grueling week of interviews, in which he wore the same clothes every day and sat still in a chair for hours at a time under bright lights and cameras, answering difficult questions — 2,000 in all — that brought up a painful past.

“It was very emotional. I cried initially and I don’t take to crying,” Elster said of the first time he saw his testimony played back for him.

Smith said the project could have been successful even if each survivor were asked fewer questions. But the comprehensiveness of each testimony gave each testimony extra character depth.

“If you were just going to ask the question, ‘where were you born, or what camps were you in, or what did you feel like when you were liberated,’ we could do that quite easily in 200 questions,” Smith said. “But the point to which they say, ‘So tell me about the psychological consequences of slave labor,’ or something like that, then you have a more nuanced question, for which [the holographic display] has an answer.”

Elster, now 85, is quite pleased with the final product, and is confident his testimony will resonate with younger generations. On its own, the Illinois Holocaust museum, the third largest in the world and created partly in response to an attempt by neo-Nazis to march in this heavily Jewish suburb in the late 1970s, welcomes 60,000 students and educators annually.

“As survivors, we’re concerned and afraid that our pain, our loss, our surviving will be forgotten or homogenized,” he said. “They’ve created something that’s going to live on much after we’re gone.”

A New York Times documentary about the project, called “116 Cameras” and making the rounds of film festivals, shows the space-age contraption in which they film the survivors.

The Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City began piloting the project in July. Its two holograms will be on display for the public through April.

Additional pilots, open to the public, are being tested at the Sarah and Chaim Neuberger Holocaust Education Centre in Toronto and the Holocaust Museum in Houston. The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., ended its pilot on Labor Day after several months. The Candles Holocaust Museum and Education Center in Terre Haute, Indiana, also has piloted the project and plans to install a permanent display that will open this fall.