At illegal Amona outpost, promises of compromise and hints of violence

Published December 15, 2016

Eli Greenberg sitting outside his home in the West Bank outpost of Amona, Dec. 13, 2016. (Andrew Tobin)

AMONA, West Bank (JTA) – The residents of this illegal hilltop outpost rejected compromise late Wednesday, but insist they are not uncompromising.

ADVERTISEMENT

Sitting on his couch in his adapted mobile home on a hill in the northern West Bank, where he and his wife live with several of their eight children, Eli Greenberg portrayed the residents of Amona as more moderate than those who have come to help prevent the settlement’s evacuation.

“A lot of people here are really simple, normal guys from the Jerusalem suburbs, if you can call us a suburb. The visitors are more hardcore activists, holding the more religious stance of you’re not allowed to give anything away from the Land of Israel,” he said. “This is a very clear theological approach. We hold that as well, but let’s say we have more variables in the equation.”

Amona, comprised of a few dozen caravans near the settlement of Ofra, is among about 100 outposts built in the West Bank without permission but generally tolerated by the Israeli government. That indulgence ended when Israel’s High Court of Justice ruled in 2014 that Amona was built on land illegally appropriated from its Palestinian owners and had to be evacuated within two years. A subsequent High Court order set Dec. 25 as the evacuation date.

The government had offered to relocate the residents to a nearby plot of land in exchange for a promise to leave their homes peacefully, but they overwhelmingly voted to turned down the deal. Although the evacuation of Amona would hardly alter the reality of Israeli settlement throughout the West Bank, it has become a major flash point on the right and the left.

Just before announcing their decision, Amona residents called for help from Israelis to protect the homes of the approximately 40 families living there.

ADVERTISEMENT

“We call for all the nation Israel to come to Amona and protest the wrongdoing of a Jewish settlement’s destruction,” one text message said.

As the terms of the government’s offer suggests, the threat of an ugly evacuation – with scenes of security forces dragging Jews from their homes or even violent clashes – is the main bargaining chip for Amona residents. While stopping short of calling for violence, the residents have not ruled it out. They have also warned that they cannot control the hundreds of mostly young people who have converged on the outpost at their urging.

Amona’s cluster of mobile homes, located atop a hill in the northern West Bank, Dec. 13, 2016. (Andrew Tobin)

“We intend to make the evacuation the worst scenario possible and to film it,” Greenberg, who has served as an unofficial spokesman for Amona, said Tuesday. “I cannot hold accountable anyone who starts freaking out because people are taking him out of his home. I don’t know how I will react when I see soldiers or policemen here at my door.

“I will film it, and I will make a great movie out of it, and I will make it as painful to the politicians as possible that they kicked me out of my house, and I will try to make them pay as much as I can politically and make them reconsider 70 times before they even think about creating a scenario like that again.”

Young men dancing and singing in the Amona synagogue, Dec. 13, 2016. (Andrew Tobin)

Hundreds of young Israelis have come to Amona this month to oppose its evacuation. Many come for daylong visits, while others camp out in greenhouses and shacks that residents have erected, braving frigid nights and rain. Since the storms started deluging Israel last week, some Amona residents have let visitors sleep in their homes.

At the local synagogue, where a table with coffee dispensers and papers cups had been set up, young men studied Jewish texts and prayed, some wrapped in tallit and tefillin. After afternoon prayers on Tuesday, dozens of young men locked hands and danced and sang in a circle in the synagogue.

Afterward, four young men with large knitted kippot and thick beards and payot huddled at a table piled with Jewish texts. Asked how long they had been in Amona, one dark-haired young man replied over his shoulder, “Happy holiday, Happy New Year, see you later.”

Naomi and Elisheva, 18-year-old students from a religious girls school in the settlement of Maale Levona, were walking around Amona, where they had been camping for a week. Their headscarves and long skirts were covered with dust and reinforced with heavy pants, coats and scarves.

“We will be here when the police come,” Naomi said. “We fill fight them to protect the Land of Israel.” She estimated “well over 100” of the 300 people camping at Amona would physically resist its evacuation.

Greenhouses providing shelter to the hundreds of young people who have come to protest in Amona, Dec. 13, 2016. (Andrew Tobin)

Like Greenberg, many of the yeshiva students who came to Amona for the day drew a line between themselves and the hardcore activists among those who were camping out. They agreed such people had come mostly from the West Bank and opposed the State of Israel as a betrayer of Jewish law.

“There are always fanatics. They’re here,” said Michael Hermelin, 17, who visited Amona for several hours with dozens of other students from his yeshiva in the settlement of Itamar. “We know people like that. They’re like anti-Zionists.”

Walking toward the synagogue with several friends, he added: “It’s a small percentage. But when you come to a place like this, there are a lot of them because they all come here. I don’t think there’s more than 200 of them, like everywhere [in the West Bank].”

David Rappaport, 21, was studying with two friends in the Amona synagogue on Tuesday. They came to the outpost from Beit Shean in northern Israel, where they attend a “hesder” yeshiva that combines army service with Jewish study. Their yeshiva had been praying against the evacuation for a month, and rabbis and settler activists had come to speak to the students about the biblical Jewish deed to the West Bank.

Rappaport and his friends said most of the visitors wanted to resist Amona’s evacuation nonviolently. They pointed out that leading religious Zionist rabbis had called for Jews to block the evacuation of Amona but to stop short of violence.

“We come here quietly, learn Torah and go home. The extremists stay here and burn tires and hit cops and soldiers,” he said. “They are mostly young people who come from the settlements and experienced evacuation in the past. So they’re ready to fight no matter what. They don’t listen to the rabbis.”

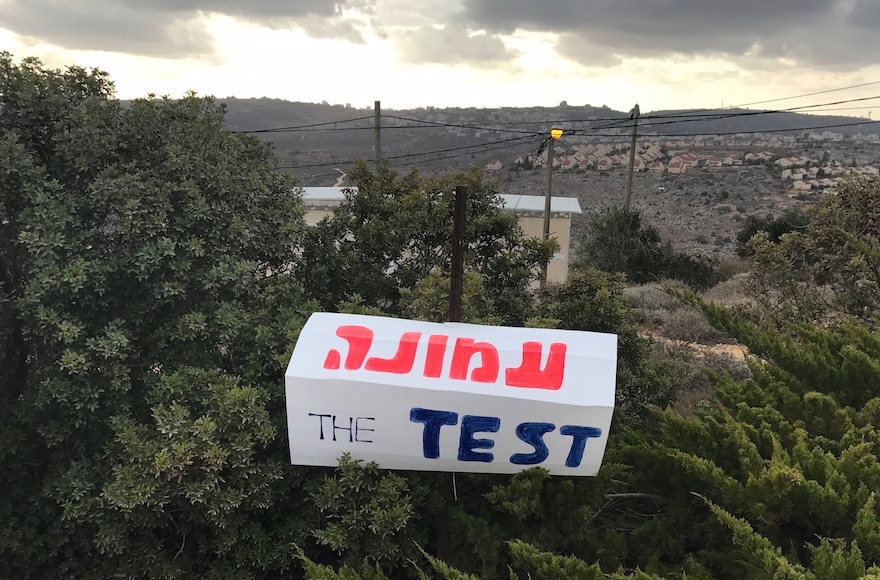

A sign saying “Amona: The Test” in the West Bank outpost, Dec. 13, 2016. (Andrew Tobin)

One of Rappaport’s friends, Eliav Amir, 21, voiced the widespread sentiment that Amona’s evacuation was not just a matter for its residents. He said all Jews had an obligation to fight the evacuation — which the Israeli media reported Thursday is expected in the coming days – regardless of what position the residents take. But Amir and his friends agreed, somewhat hesitantly, that the “unity of the people” took precedence over the land.

In their statement Wednesday night, the Amona residents said they would only accept a deal in which Israel gave its “explicit commitment to build the temporary homes and delay the evacuation until after that construction is completed.”

“We have learned from previous expulsions, we cannot count on words that are not backed by commitments,” the statement said.

The deal rejected by the residents, agreed to by the government after long internal negotiations, would have set up 40 “mobile structures” on land near Amona for at least two years. Israel would have sought to turn the structures into a ‘long-term settlement” after having the land recognized as belonging to “absentee” landlords — Palestinians who left before or during Israel’s capture of the West Bank during the 1967 Six-Day War.

The state also would have asked the High Court to delay the Amona evacuation for 30 days, and the Amona residents would have been given temporary homes in the adjacent settlement of Ofra if needed.

Mayor Abdel-Rahman Saleh at his home in the Arab village of Silwad, which borders Amona, Dec. 13, 2016. (Andrew Tobin)

Gilad Grossman, a spokesman for Yesh Din, an Israeli nonprofit organization representing the Palestinians who own land in Amona in their petition to the High Court, said Tuesday that any solution that involved moving the residents to Palestinian-owned land would be unacceptable. He said that since Amona’s founding in 1996, “everybody knew it was an illegal enterprise on private Palestinian land,” and the High Court had ruled as much in 2005, forcing the violent evacuation of several structures the following year.

Grossman said Yesh Din also was opposed in principle to the Regulations Law, which started as a way to avoid evacuating Amona. The bill, which passed its first reading in the Knesset last week, would in its current form legalize housing built by settlers on Palestinian land under certain conditions, but would not save Amona.

Abdel-Rahman Saleh, the mayor of Silwad, the Arab village that neighbors Amona and a petitioner in Yesh Din’s case, said the residents must at minimum leave the West Bank entirely.

“All the settlements are illegal. The solution that should at the least be that they go back to the 1967 borders so we can have a free state in the West Bank and Gaza,” he said over tea at his towering stone home.

“They can have a state in Israel, but this is not forever. History shows that invaders that come into this nation will be defeated.”

Saleh went on to list Israel’s gradual relinquishing of territory in the Sinai Peninsula, Southern Lebanon, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank as proof of its imminent demise.

Greenberg, the unofficial Amona spokesman, said Palestinians would only accept Israel’s presence when the state made clear it was done giving away territory. He called for annexing the West Bank and giving Palestinians a lesser form of citizenship.

In a phone call Thursday, Greenberg said the evacuation of Amona was now rumored to be scheduled for Sunday. Previously rumored dates have come and gone, but the deadline is less than two weeks away and the government has not requested another delay.

Greenberg predicted that whatever happened, Amona’s residents would be the ultimate winners.

“If Amona survives, we win, and even if Amona won’t survive, the abilities that we developed here in Amona during the last year will change the State of Israel in the coming years,” he said. “We woke up in a way, and we know that people that really want something and really know what they want can push on and achieve a lot of things.”