An elite private academy in Rio is putting pressure on the city’s Jewish day schools

Published July 9, 2018

The Eleva school is the latest project of Jorge Paulo Lemann, Brazil’s richest man. (Courtesy of Eleva)

RIO DE JANEIRO (JTA) – One of the hottest topics among Rio Jewish families today sits right across the street from both the city’s largest synagogue and the site of a future Holocaust memorial.

It’s a non-Jewish day school, directed by a Cohen with the support of a Levy, that is becoming a magnet to Jewish students — and some say a threat to Jewish schooling in the country’s second largest Jewish community.

Founded in early 2017 at a cost of $30 million, Eleva is the newest bet for Brazil’s richest person, Jorge Paulo Lemann, whose fortune is estimated at $30 billion. Lemann, who is not Jewish, is the lead investor in the school, which is housed at the plush, palace-like building of the former Casa Daros cultural center. The 130,000-square-foot school boasts a highly trained faculty, an international curriculum that emphasizes English, and ties with some of Brazil’s leading sports clubs and cultural groups.

Eleva generates a love-hate sentiment among Rio’s 30,000 Jews: The school is seen as a long-awaited El Dorado for some, and a threat to Jewish continuity by those who fear that the city’s traditional Jewish schools may be not survive the competition.

“We really expected a high [Jewish] demand due to the unusual combination we propose: a strong traditional curriculum in both Portuguese and English, the intentional development of social and emotional skills, and an intense look at global citizenship,” Marcio Cohen, Eleva’s pedagogic director, told JTA.

Cohen is a grandson of Polish Jewish immigrants and married to an American Jew, but does not identify himself as Jewish.

Eleva has some 150 Jewish students out of a total student body of 1,000. That’s more than who attend ORT, the smallest of Rio’s four Jewish day schools, only half of whose 200 students come from a Jewish background.

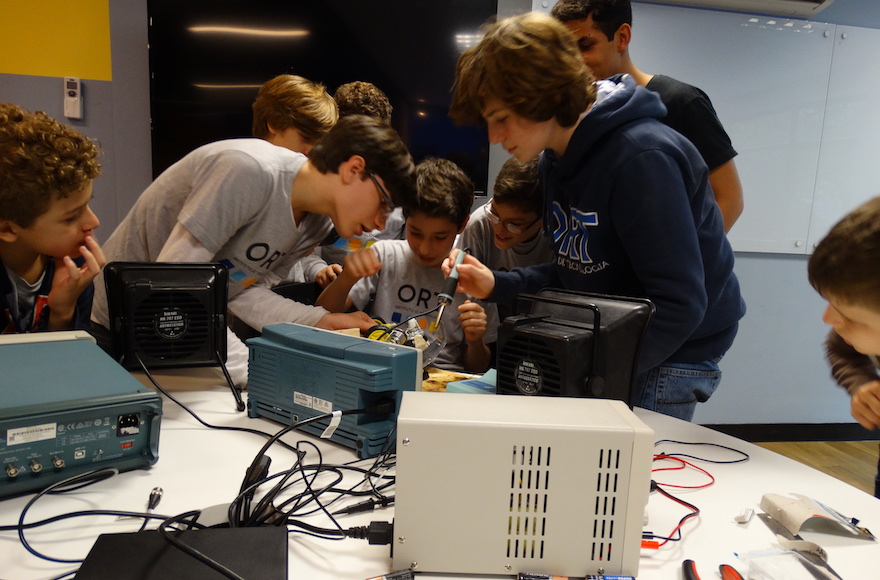

“They made a strong investment in infrastructure and have a pedagogical proposal aiming at families that expect their children to live abroad,” ORT’s administrative director, Wilson Cukierman, told JTA. “We offer something unique: We are a Jewish, pluralistic school whose mission is the academic and professional training of youths, providing them with technological mastery.”

Bilingualism at a reasonable cost – Eleva charges a monthly fee of $1,300, only $300 more than Jewish schools – seems to be one of the most precious triumphs to attract more and more Jewish families. Like most of Brazil’s upper middle class, English is a ticket for moving abroad, or at least having the option to flee the country’s shocking murder rates – nearly 65,000 a year – and economic insecurity.

“We want our kids in the future to be able and ready to choose between a Brazilian university and any international institution,” said Jonny Haiat, a Jewish father of three students at Eleva. “Also, it’s a different paradigm. Eleva is much more open-minded and values individuality and a broader development.”

The Rio Jewish federation does not reveal numbers of students enrolled in Jewish day schools. Education director Michel Ventura acknowledges that those numbers have dropped, but prefers to minimize the impact of Eleva.

Students playing with technology at ORT, the smallest of Rio’s four Jewish day schools. (Courtesy of ORT)

“It’s related to several reasons, such as assimilation and immigration, including aliyah to Israel. But I do not see an exodus,” Ventura told JTA. “Big projects like Eleva will only have results in 10 or 15 years. But what is the project behind it? A career-oriented one?

“Schools like Eleva exclude students who do not score a minimum,” Ventura said, “whereas Jewish schools absorb children of any intellectual and financial level.”

Eleva’s pedagogical coordinator, Tatiana Levy, disagrees. A Jewish mother herself, she believes Jewish schools need to rethink their concept and reposition themselves in the country’s educational environment, where powerful private groups have been replacing nonprofits.

“We have students from 45 different schools. The Jewish school environment is much more protected, but you end up ignoring a lot of stuff,” she said. “Many parents want their children to get familiar with a multiplicity of cultures and religions.”

Levy, who attended Eliezer Max Jewish school during her childhood before spending a large part of her life abroad, believes that bilingualism is only one of the reasons that many Jewish parents have chosen Eleva.

“Jewish schools teach Hebrew, a language with a more restricted use,” she said. “Our second language is English. But it’s beyond that, it’s about our contemporary education, otherwise these same parents would take their kids to the American or the British schools.”

Eliezer Max’s president, Fabio Beildeck, celebrates the fact that only 15 students among the school’s 500 transferred to Eleva.

“Families were enchanted by the … novelty, heavily influenced by marketing. They felt they just couldn’t miss it,” he said. “In addition to the Jewish concept, Eliezer has a consolidated and coherent pedagogical approach, something that a new school will take a few years to reach.”

And just as they might at a Friends school or similar elite academy in the United States, parents acknowledge the trade-off between Eleva’s reputation and its lack of Jewish content.

“I have always dreamed of my daughter studying in a Jewish school like I did, but I was delighted with Eleva’s proposal and innovation,” said Nicole Abramoff, whose older daughter attends Eleva.

“Subjects are modern, useful, practical and participative. Teachers don’t just write on the board for kids to copy. It’s totally computerized, each kids receives a Chromebook, they have coding, speech and citizenship classes. And they’ll leave the school fluent in English.”

But Abramoff’s daughter misses her old friends every day.

“It’s not our final decision,” Abramoff said. “It’s possible that my baby daughter will never come.”

With two kids at Eleva, Rafaela Carpilovsky tries to compensate by celebrating Jewish holidays at home and attending synagogue regularly.

“But it’s not the same thing like being at a Jewish school, where there is a daily involvement with the Jewish culture and history,” she acknowledged. “Those families that have this as a priority won’t change to Eleva.”

When Marcio Sukman’s two kids were accepted at two of Rio’s very few public schools still considered prestigious – known as Pedro II and CAP UFRJ – he was thrilled about a “more diverse education.” But it’s been tough on the family.

“The coexistence is much more complicated,” he said. “Unlike at a Jewish school, where families already know each other and where we form very strong bonds for a lifetime, cultivating friendships in public schools becomes more difficult, and obstacles need to be overcome.”

A view of a classroom at Liessin, Brazil’s largest Jewish day school. (Courtesy of Liessin)

The children of Sukman, Haiat, Abramoff and Carpilovsky have all moved to Eleva after attending their first school years at Liessin, Brazil’s largest Jewish day school. It has some 1,300 students – down from 1,400 just a few years ago. Liessin has two campuses, one of them in the Barra neighborhood, where Eleva is slated to open its second unit in 2019.

Liessin’s president, Daniel Szwarcwald, said his school has nothing to fear about Eleva or any other school.

“We have just started to hear that parents who took their kids to Eleva are thinking of coming back,” he said. “The doors of all Jewish schools are always open, so people who leave to try something new know that they can return if they have a bad experience.”

Szwarcwald boasts about his school’s Jewish content, from festivals and rituals, to participation in the March of the Living trip to Poland and Israel, to the Pikudei project, where students explore their Jewish family histories.

“Liessin has something Eleva will never be able to have: a Jewish identity that permeates the whole curriculum and the whole school life,” he said.

The president of TTH-Barilan, Rio’s only Orthodox school, celebrates the fact that only two of his students left for Eleva. But transfers are always a concern, said Rafael Antaki. The school recently gathered some $700,000 in a crowdfunding campaign to support scholarships for some 30 percent of the schools’ 400 students.

“How to reduce dropouts is the million-dollar question,” Antaki said. “You must succeed to make both kids and parents value the importance to be part of the Jewish community. If they don’t value the Jewish element, be it religious or social, they will leave. We can’t compete with the non-Jewish schools.”