Amid neo-Nazi surge, Jewish groups applaud Greece’s Holocaust denial ban

Published September 11, 2014

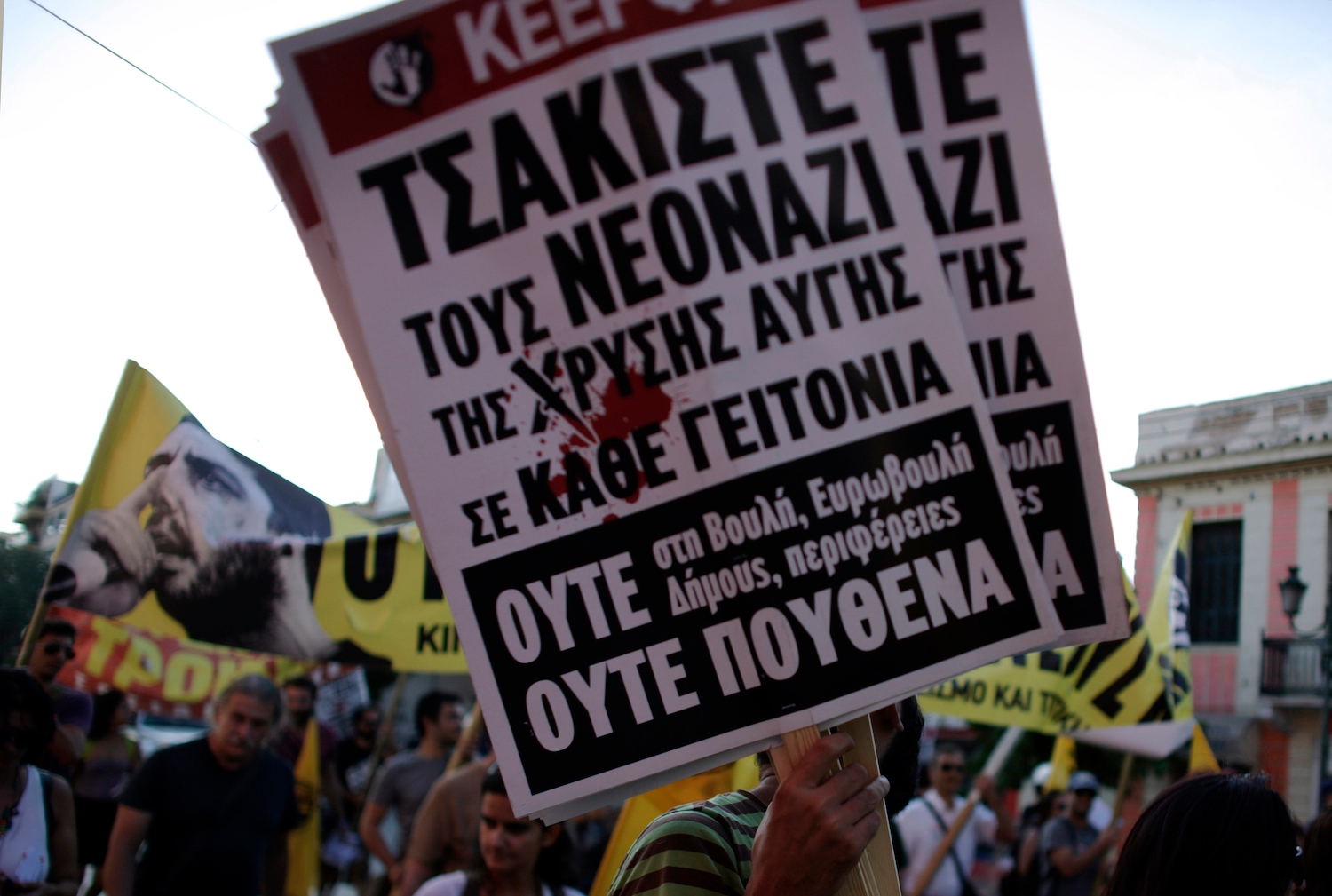

Anti-fascist protesters holding a banner in front of the Athens municipal amphitheater during a swearing-in ceremony, Aug. 29, 2014. (Milos Bicanski/Getty Images)

ADVERTISEMENT

ATHENS, Greece (JTA) — Jewish groups say the passage of a bill banning Holocaust denial and imposing harsher penalties for hate speech is an important milestone in the fight against Greece’s rising neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party.

“This comes very late, but not too late,” World Jewish Congress CEO Robert Singer told JTA.

Greece’s parliament passed the bill Tuesday following more than a year of political wrangling.

Riding a wave of fear and despair brought on by Greece’s devastating economic crisis — coupled with a large influx of illegal immigrants from Africa and Asia — Golden Dawn emerged from obscurity in 2012 to become the country’s third largest political party, with 18 members of parliament.

Golden Dawn, which uses Nazi imagery, has been blamed by the government, prosecutors and law enforcements for hundreds of xenophobic attacks. The incidents include the killings of at least four Pakistani immigrants and the murder of Pavlos Fyssas, a noted anti-fascist Greek rapper known as Killah P.

The new law increases jail time to three years for instigating racist violence and imposes fines of up to 26,000 euros (about $34,000) for individuals and up to 100,000 euros (about $130,000) for groups convicted of “inciting acts of discrimination, hatred or violence.” It also criminalizes denial of the Holocaust and other recognized genocides, with the same penalties.

In a move that will allow the government to target political groups like Golden Dawn, organizations found to incite racism can be barred from receiving state funds. However, the law cannot be applied retroactively.

ADVERTISEMENT

Anti-racism laws dating back to 1979 did not provide for prosecuting groups or parties that incited bias crimes. They also barred police from investigating suspected hate crimes if the victim chose not to press charges.

“We have anti-racism laws already, but the reason they were not applied was that immigrants, for example, were afraid to report the crimes because they did not hold proper travel documents, lived here illegally and feared deportation,” Justice Minister Haralambos Athanasiou told parliament ahead of the debate on the legislation.

There were also no prior provisions against Holocaust denial. So there was little the authorities could do when a Golden Dawn lawmaker proudly declared himself a Holocaust denier or when party leader Nikolaos Michaloliakos, in a television interview, denied the existence of gas chambers at Nazi death camps.

Following the 2013 murder of Fyssas, which Greek prosecutors blamed on Golden Dawn activists, many Golden Dawn leaders and lawmakers were arrested and accused of running a criminal organization. Their trials are scheduled for December.

Even with top party leaders jailed, including Michaloliakos, Golden Dawn maintained its popular support in recent municipal elections.

“We really hope the law will limit racist and anti-Semitic statements and will deter Holocaust deniers, who have multiplied in the last two years, including inside parliament,” said Victor Eliezer, the secretary general of the Central Board of Jewish Communities in Greece.

Some 5,000 Jews live in Greece today. The prewar community of some 78,000, most of whom lived in the northern port city of Thessaloniki, was almost entirely wiped out in the Holocaust.

It is also hoped that the law will curb expressions of anti-Semitism. A recent Anti-Defamation League survey found Greece to be the most anti-Semitic country in Europe, with 69 percent of the population holding anti-Jewish views.

The new law brings Greece in line with most of the other European Union countries, which have barred Holocaust denial and impose similar jail sentences for inciting racial or ethnic violence.

An initial draft of the measure failed to garner enough support after right-wing elements in Prime Minister Antonis Samaras’ New Democracy party proposed excluding the Orthodox Church and the military or police from prosecution under the law.

Other holdups were over which genocides to recognize, whether or not to include provisions for homophobic violence and a petition by 139 academics against the Holocaust denial clause in the name of free speech.

In addition to the Holocaust, the new law includes the mass killings of Armenians, Black Sea Greeks or other Christians in Asia Minor during the waning days of the Ottoman Empire. Under the law, inciting violence or discrimination for homophobic reasons is illegal, but provisions allowing for civil unions of gay couples were removed.

In a measure of how problematic the law is, only 99 of the 300 members of parliament turned up for the final vote, with 55 voting in favor.

“What is xenophobia? The railings at my home stopping a Pakistani, or any foreigner, from raping my wife or killing me?” Golden Dawn lawmaker Michail Arvanitis told parliament, according to Reuters. “Discrimination is a fact of life.”

But the nation’s Jews, its Jewish leaders and others who support the new legislation see things much differently.

“We hope [the law] will be applied rigorously by the courts,” the WJC’s Singer said.

“However, more efforts will need to be undertaken if the fight against extremist forces such as Golden Dawn is to be successful,” he said, but did not mention specifics.

![]()