(JTA) — My parents, children of Eastern European Jewish immigrants, were named Irving and Naomi. They named their three sons Stephen, Jeffrey and Andrew. My kids’ names are Noah, Elie and Kayla.

Our first names capture the sweep of the American Jewish experience, from the early 20th century to the early 21st. At each stop on the journey, kids were given names — sometimes “Jewish,” sometimes not — that tell you something about how they fit both into Jewish tradition and the American mosaic.

A new study from the Jewish Language Project at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion charts how Jewish names have evolved over that history and what they say about American Jewish identity. For “American Jewish Personal Names,” Sarah Bunin Benor and Alicia B. Chandler surveyed over 11,000 people who identified as Jewish, asking about the names they were given and the names they were giving their children. (They also consulted several databases, including the indispensable Jewish Baby Names finder from my colleagues at Kveller.)

ADVERTISEMENT

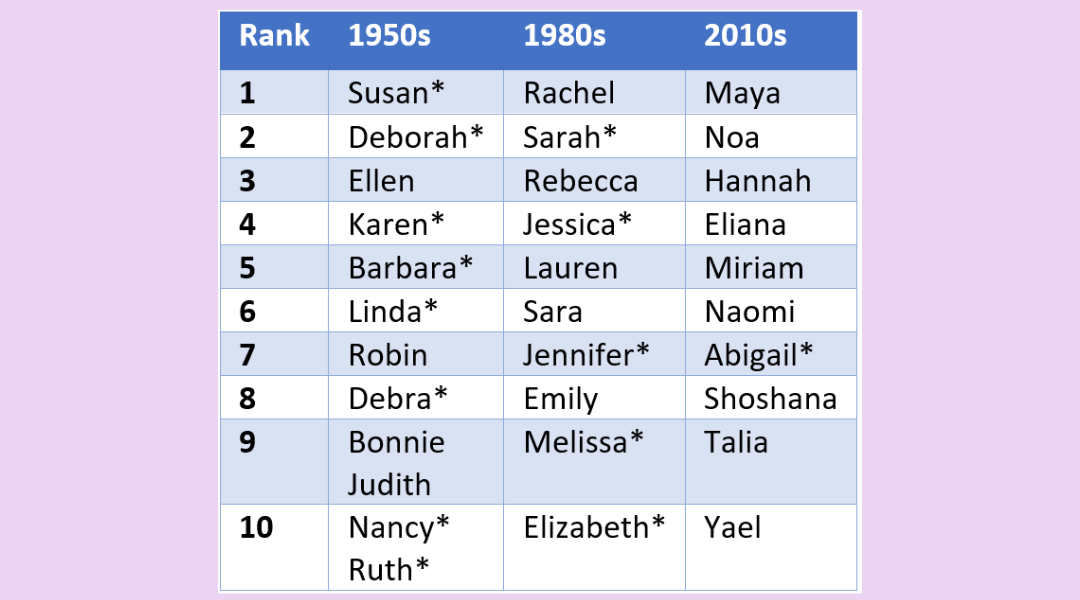

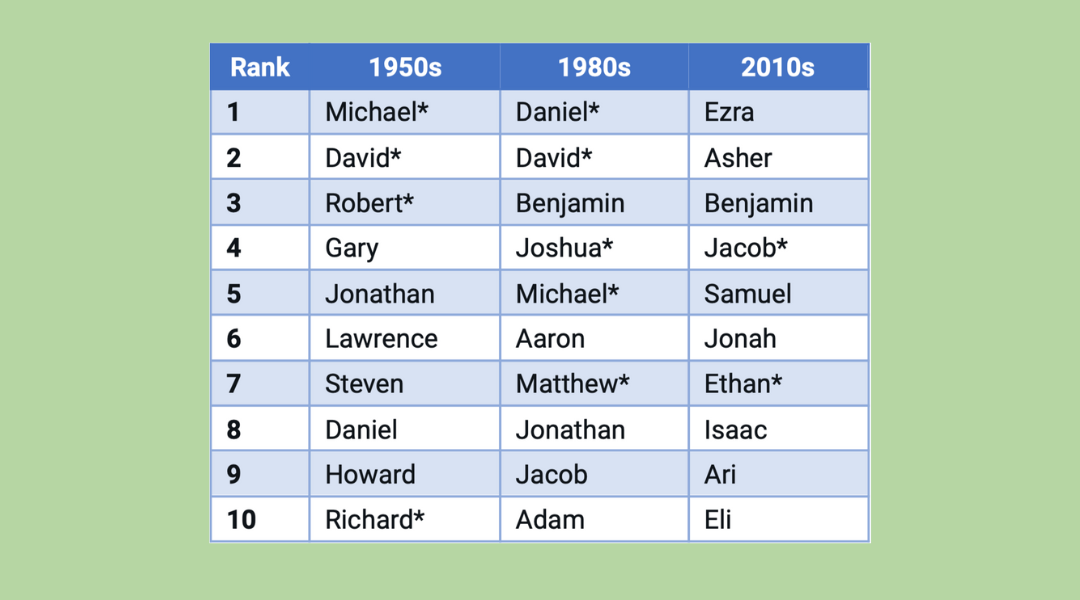

The results suggest my family’s first names were typical: In the century since my grandparents (Albert, Sarah, Sam and Bessie) arrived at Ellis Island, and after an era of Susans and Scotts, American Jews became more and more likely to give their children Biblical, Hebrew, Israeli and even ambiguous names that have come to sound “Jewish.” “The top 10 names for Jewish girls and boys in each decade reflect these changes,” the authors write, “such as Ellen and Robert in the 1950s, Rebecca and Joshua in the 1970s, and Noa and Ari in the 2010s.”

It’s a story about acculturation, say the authors, but also about distinctiveness: Once they felt fully at home, Jews asserted themselves by picking names that proudly asserted their Jewishness.

On Thursday, I spoke with Benor, vice provost at HUC-JIR in Los Angeles, professor of contemporary Jewish studies and linguistics and director of the Jewish Language Project. Our conversation touched on, among other things, today’s most popular Jewish names, the Jewish names people give to their pets and the aliases many people give to Starbucks baristas. Mostly we spoke about the ways Jewish tradition and American innovation are expressed in our first names.

This interview was condensed and edited for clarity

ADVERTISEMENT

Jewish Telegraphic Agency: I want to start with the big takeaway from your study: “Younger Jews are significantly more likely than older Jews to have Distinctively Jewish names.” Does that sound right?

Sarah Bunim Benor: Definitely. The thing that I think people are going to be most excited about is the chart showing the most popular names by decade. If you look at the 1950s, you have girls’ names like Barbara, Linda and Robin. These are not distinctively Jewish and not biblical. And then by the 1980s, it’s very biblical: Sarah, Rachel, Rebecca. By the 2000s the top three names are Hannah, Maya and Miriam. And by the 2010s you get these names that are either biblical or modern Hebrew or coded Hebrew: Noa, Eliana, Naomi.

Top 10 girls’ names among Jewish respondents to the “Survey of American Jewish Personal Names,” by decades of birth. (An * indicates that the name is also in the overall U.S. Top 10 for that decade.) (www.jewishlanguages.org)

You note that today most of the top 20 Jewish girls’ and boys’ names are English versions of Biblical names. But that doesn’t account for all the “Jewish” names in the study, which range from “Hebrew Post-Biblical,” like Akiva, Bruria and Meir, to the “ambiguously Jewish,” like Lila and Mindy. How did you decide which names are distinctively Jewish?

We based our judgment on our respondents’ judgments. We had them rate their own names, and ask, If you met someone with your name, how likely would you assume that they were Jewish on a scale of zero to 10? And we had them do the same for a sample of, I think it was 13 male names and 13 female names.

By which you discovered that there are currently “names of no Jewish origin” that have come to be seen as Jewish.

Definitely. And the ones that I find most interesting in that category are the coded Jewish names like Maya and Lila and Eliana, and other names that are popular in America, like Emmett. They have these coded Jewish meanings. [“Maya” is thought to relate to mayim, the Hebrew word for water; in Hebrew, “lilah” means “night” and “emet” means “truth.”] And Evan [“rock” in Hebrew and “John” in Welch] is another example where we American Jews interpret these American names as Jewish names because they have homologous interpretations in Hebrew.

Eliana, for example, is not of Jewish origin, but it sounds exactly like “li ana,” my God answered. And so it’s a beautiful name. And it’s become pretty popular among Jews.

I think about my father’s generation — the generation of Irvings and Stanleys and Sylvias. And they became distinctively Jewish names without being Jewish names, right? Was that about people wanting to assimilate, but also not wanting to disappear into the mainstream?

When immigrant parents gave their children names like Irving and Stanley, it was an attempt to Americanize, but also they chose names that their neighbors or friends were giving their babies, and so it ended up that some names turned out to be seen as Jewish names.

I’m just trying to think what was inside my grandmother’s head when she named my father Irving — perhaps she wanted the child to sound like an American but not necessarily like a gentile.

She might not have thought of it as sounding like a gentile name. She might have thought of it as sounding like an American Jewish name.

You compared the names of your respondents and the names of their children. What does this tell us about naming trends?

Across generations, groups increased in their Jewish distinctiveness over time. Take, for example, names we categorize as “of no Jewish origin,” like Richard and Jennifer. There is a significant drop between the older generation and the younger generation when it comes to such names.

Meaning the Richards and Jennifers are not naming their kids Ellen and Steven but Maya and Ezra.

Yes. Although there are still many Jews who do use names of no Jewish origin, it’s much less than it was before.

We have data on name changing, and I was surprised at how few people reported changing their name to one that sounds less Jewish. The name changes that we heard were more about changes in gender presentation and changes for various other reasons but not to sound less Jewish.

You talked about 1970 as a sort of pivot point, in which a decline in Jews changing their last names is replaced by an increase in baby names considered more Jewish. Remind us of that history.

There’s a great book about this, “A Rosenberg by Any Other Name,” by Kirsten Fermaglich. She found that Jews in the middle of the 20th century were changing their names — because of antisemitism, because they weren’t able to get into universities or stay at hotels or get certain jobs because of their names. It was a way of integrating into American society, not necessarily as a way of assimilating. Just because they changed their names didn’t mean that they were now not identified with Jewish communities. They tended to still be engaged.

And then in the ‘60s and ‘70s, it became more acceptable to have a distinctive ethnic identity. Antisemitism diminished significantly, but it was also part of a broader American trend to highlight your ethnic distinctiveness. Jews participated in that in numerous ways, including a tendency to give their babies distinctive names.

That theme runs through your discussion: the back and forth between acculturation and distinctiveness.

That has been the case throughout Jewish history. Wherever Jews have lived, they have had to come up with a balance between acculturation and distinctiveness, and in some cases, it was much more on the acculturation side. In some cases, it was much more on the distinctive side.

Top 10 boys’ names among Jewish respondents to the “Survey of American Jewish Personal Names,” by decades of birth. (An * indicates that the name is also in the overall U.S. Top 10 for that decade.) (www.jewishlanguages.org)

You describe how the distinctiveness of Jewish baby names rises with the parents’ engagement in Jewish life, including visits to Israel, synagogue attendance, denomination. You also note that “rabbis and cantors have the highest rates of children with Distinctively Jewish names, followed by Jewish educators and Jewish studies scholars,” and that Orthodox Jews are more likely than non-Orthodox Jews to pick names high on the scale of Jewishness. Let’s talk about how these trends increase across levels of engagement.

Another really striking image to me is the time spent in Israel. Having a distinctively Jewish name and especially having a modern Hebrew name increase with how much time the parents have spent in Israel. And you get similar spreads for other things like denominations. Something like 69% of haredi or “black-hat” Jews give their children distinctively Jewish names, compared to 35% of Modern Orthodox. So there is a huge split even among the Orthodox. And then you know, for other denominations, it is even lower than that.

I was surprised how many people still have Jewish ritual names in addition to their given “English” names — in my case, I am Avrum on my wedding contract and when called up for synagogue honors. Wasn’t it over 90%?

Yes, 95% of the respondents say they have a ritual name, but a lot of those are the same name as their non-ritual name, like “Sarah.” That does reflect our sample being more engaged in Jewish life than the average random sample of Jews. What’s interesting here is the Orthodox versus non-Orthodox children, where 64% of Orthodox children have exactly the same ritual name as their given first name, which means that they’re giving their children distinctively Jewish names, and non-Orthodox children only 30%.

The ritual names convention, which for a long time was reserved for boys, opens up a whole discussion of gender — including the fact that there are just so many more male biblical names than female names.

If you look at the names that are most popular among Jewish respondents by decade of birth, you see that the girls’ names include some modern Hebrew names that are not biblical, like Talia and Noa, and that among the most popular male names from the 2010s, the names are almost all biblical names.

You also talk about Sephardi/Mizrahi and Ashkenazi naming conventions, which I think most people associate with the idea that Ashkenazim don’t name a child after a living relative. Your survey confirms that that tradition is holding pretty strong.

To some extent, although I was kind of surprised how many Sephardi respondents exclusively named children in honor of deceased relatives — like 40% or more of those who identify as only Sephardi or Mizrahi. They have the highest rate of naming after living honorees, but they also have the highest rate of naming after no honorees. Granted, our sample of Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews is pretty small, despite our efforts to get respondents who aren’t Ashkenazi.

The study discusses “Starbucks names.” Is that a term of art in the social sciences?

It refers to the idea of a name that you use for some service encounters [such as buying coffee] that’s different from your own, because your own name is hard to spell or you don’t want to hear your name called in a public place. I found that Jews with distinctively Jewish names were much more likely to use a Starbucks name sometimes than those who don’t have distinctively Jewish names. But I was also surprised that some people who don’t have distinctively Jewish names also use a Starbucks alternative that’s more Jewish because they want to identify in public as Jewish.

And then there is the Aroma name, named after the Israeli coffee chain. That’s where Americans give a Hebrew spin to their English name that they know the Israeli barista is going to mispronounce.

Yeah, exactly. That was fun. I hadn’t heard that term, but some of the respondents use it. A Kelly said she uses “Kelilah” in Israel.

Does Starbucks naming actually extend to code-switching elsewhere? I’m thinking of the generation that included people like, say, Rabbi Irving Greenberg, who goes by “Yitz,” short for Yitzhak. I think that generation — Rabbi Greenberg is 89 — did code switch to some degree.

That’s right. Or Bernard Dov Spolsky [a professor emeritus in linguistics at Bar-Ilan University], who passed away two weeks ago. He was from New Zealand and his English name was Bernard and he published under Bernard Spolsky, but he went by Dov in Jewish circles.

What’s the importance of studying names? What do they reveal about the community?

Names are such an important part of how we present ourselves to the world. People spend months before they give birth or adopt their child coming up with a list of names and how they want to represent themselves and often how Jewishly they want to represent themselves. And people also often think about their names later in life. Do they want to go by the name they were given or go by a nickname? Or do they want to completely change their name?

When you look at this data set, what does it tell you about American Jewry at this moment?

There are two ways to answer that. One is through the acculturation and distinctiveness lens. I think the data show that Jews have become more distinct over time in the last 60 or 70 years or so. You can also look through the lens of tradition and innovation. Are American Jews using naming practices that have been parts of Jewish communities for centuries, or are they coming up with new traditions? Most of the naming practices reflect traditions that have been part of Jewish communities for centuries, with some modern spins. Even the Starbucks name: When Hadassah goes by Esther in the Purim story, you can think of that as a historical Starbucks name.

And pet names: You found that 32%, a sizable minority, of Jewish pet owners give their pets names they consider Jewish, like Latke or Feivel or Ketsele.

I don’t know if Jews historically used Jewish names for their pets. I don’t know of any study of that. But the fact that that is such a common thing among contemporary American Jews may reflect the importance of pets in our culture, but also the desire of Jews to highlight their Jewishness, even if their children don’t have distinctively Jewish names. That’s another way that they can present themselves to the world as Jewish.

—

The post A news study explains why Starbucks can’t spell your Jewish name appeared first on Jewish Telegraphic Agency.