A ‘Nazi love story’ about a mass murderer who got away

Published March 30, 2021

(New York Jewish Week via JTA) — I first met Philippe Sands when he was promoting his 2015 documentary “My Nazi Legacy: What Our Fathers Did.” It told the story of Niklas Frank and Horst Wächter, two men whose fathers were among the Nazi perpetrators of the Holocaust. It was a study in contrasts: Frank acknowledged the guilt of his father, Hans, and denounced him; Wächter, hunkered down in his family’s crumbling castle, insisted his father, Otto, was a good man doing his best in a bad situation.

The film might have seemed a temporary detour in Sands’ career as an international lawyer specializing in genocide and human rights. But “My Nazi Legacy” was only the start of his journey into the themes of complicity and culpability. He followed up in 2016 with “East West Street: On the Origins of Genocide and Crimes against Humanity,” part family memoir, part deeply researched examination of the Jewish legal scholars whose ideas led to the prosecution of Nazi war criminals — including Hans Frank, the governor general of occupied Poland — at Nuremberg.

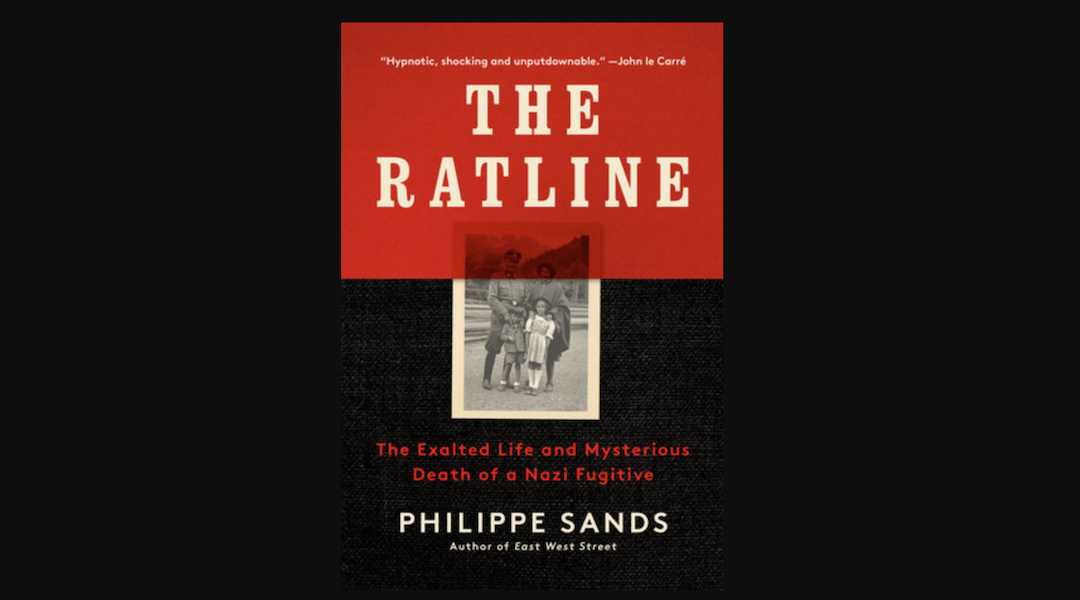

In his new book, “The Ratline: The Exalted Life and Mysterious Death of a Nazi Fugitive” (Knopf), Sands returns to Horst Wächter and the father he barely knew but refuses to renounce. As the Nazi governor of Galicia, Otto Wächter built the Krakow ghetto, oversaw the liquidation of the Lemberg (Lviv) Jewish community and was responsible for the deaths of more than 130,000 people — including Sands’ extended family. Unlike Hans Frank, however, Otto Wächter would escape justice.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The Ratline” tells how both the Catholic Church and the Allies were active in shuttling unrepentant Nazis to new lives in the West; how Otto Wächter and his wife, Charlotte, appeared to justify their shocking crimes against humanity; and how Horst Wächter, still living in his castle, still refuses to admit the truth about his father.

Sands spoke to The Jewish Week from his home in London. This interview has been condensed for length and clarity.

You’ve been involved with Horst and this story for a really long time. Tell me about the emotional toll of being so deeply entwined with these Nazis’ families.

ADVERTISEMENT

I wouldn’t use the word toll. Overall it’s sort of been liberating. I grew up in a family where these things were not talked about. Parents and grandparents don’t want to burden their children and grandchildren with the horrors of their own experience. When I went to Lviv in October 2010 with my mother, my son, my aunt, I just thought I was going for a one-off. I hoped to find my grandfather’s house. I never expected anything to come of it. But one thing led to another and, as you know, two books. The cases that I work on run for years and years, and I tend to like to get very much into the detail.

The main thing is, I think it’s been a project about identity: just understanding who we are and where we came from. I think it’s an extraordinary cast of characters, and a privilege to have met and gotten to really know Niklas and Horst as people from the other side.

Even when Horst refuses to recognize his father’s role in perpetuating the Holocaust?

He is in a state of denial. He’s not an anti-Semite, he’s not a Nazi, he’s not a Holocaust denier. He’s basically a little boy who has been deeply damaged by that period and is struggling to repair things. I don’t like his conclusions, I don’t agree with his conclusions. But I try to understand where he’s coming from.

(Knopf)

Remind me how your family story intersects with Otto von Wächter’s.

My grandfather was born in Lemberg, Poland, now Lviv, Ukraine, in 1904. He left in 1914 with his mother and his two sisters, and went to Vienna. His father and brother had died in the opening year of the First World War, and he left behind a huge family in Lemberg. He went back once in 1923. There was a family of about 80. Wächter became governor of the Galicia district and he oversaw the Final Solution there, wiping out my family.

Wächter’s story intersects another way: He entered the University of Vienna law school in 1919 in the autumn at exactly the same time as Hersch Lauterpacht, who invented the legal concept of crimes against humanity. Twenty-five years later, Wächter was responsible for the murder of Lauterpacht’s entire family, who were also based in Lemberg.

Your book tells a number of intersecting stories, including how Otto and his wife, even when he is hiding out in Rome after the war, kept up this loving correspondence. What enabled you to get inside what you at one point call, tongue in cheek, a “Nazi love story”?

I met Horst at the end of 2011 and frankly for the first four or five years, the only thing I’m interested in is what Otto did in Vienna, in 1939, and what he did in Lemberg. He’s the unknown name from this period, the one who has been airbrushed out of history. And that’s what I was interested in. Horst gave me a trove of materials in late 2014, early 2015, but he apparently decided I had inaccurately dealt with the documents and that I had withheld all the ones that show the goodness of his father. So he asked the U.S. Holocaust Museum to put the materials on its website.

Figuring that would exonerate his father.

But all of a sudden, because his mother’s diaries and letters were all beautifully kept and organized by year, you could see what happened after the ninth of May, 1945 [the surrender of Nazi Germany]. What emerged from the letters was this extraordinary account of escape, in two parts: The three years Otto spends hiding in the mountains with this SS man named Buko Rathmann – who I got to meet, and which was pretty wild, with his picture of Adolf Hitler on his bookshelf. And then the second part is Rome, where Otto and Charlotte communicate in code because they were very worried that they were being surveilled by the Americans, which, as it turns out, they were. I think the Americans knew everything, literally within half an hour of him arriving in Rome.

What are your emotions in handling this intimacy between people we don’t want to see as human?

You’ll notice I don’t refer either to Hans Frank or Otto Wächter or their wives — who I think are deeply complicit – as monsters. They did monstrous things, they did crimes on the most grotesque scale imaginable. But they were also capable of decency and humanity, and love and affection and generosity. And this is the difficult part. You and I could sit at a dining table with Wächter or Frank and have a perfectly civilized and probably quite a genial evening. What I consciously wanted to do was explore the human side because what troubles me the most is how can people who are intelligent, cultured, educated, religious, get involved in mass murder on an industrial scale. How does that happen? That’s the great mystery that I think we all want to understand.

I think the love story part is important for another reason: I think an untold story of the Nazi Holocaust is the role of the spouses. We’ve always focused on the ones who were at Nuremberg, the ones who had committed suicide or were caught and tried or escaped. But they weren’t on their own. They’d come home every day, and they’d have a nice supper and they’d look after the kids and they’d go to the opera and go to concerts and have dinner with their friends and have a regular life. The wife generally facilitated that.

You show the complicity of the Catholic Church, and also of the United States, in allowing Nazis to escape justice. What are the forces that allow the rules of the game to change immediately after the war is over?

Communism. Bolsheviks. What’s the one thing that unites the Vatican, Italian fascists, the British and the Americans? Italy was ground zero, the launching pad for the Soviets in Western Europe. From the materials that [University of Florida historian] Norman Goda helped me get, and for which David Kertzer [of Brown University] filled in the gaps, the fear of communism meant that you would turn a blind eye. The Nazis were the worst of the worst, and all of a sudden they’re our friends because they’ve got Rolodexes and they can help us take on the Soviets. And I must say this: I was just really shocked. I mean, like you, I sort of knew the Werner von Braun story. But it’s one thing to recruit scientists and another to recruit mass murderers.

Otto Wächter died in a Rome hospital in 1949 while he was still in hiding and hoping for a way out of Europe. The Austrian bishop in Rome who assisted him, Alois Karl Hudal, is also the one who later asserts that Wächter was poisoned, perhaps by a Jewish hit squad. Did you come to some closure on that point?

I thought I’d come to closure. And then the letters start coming in.

Horst’s belief that his father was poisoned is premised on his mother’s belief that her husband was poisoned, which is in turn premised on a memoir published by Hudal, which I had thought was entirely self-serving. He had just been booted out of his job for harboring Nazi war criminals, so he spins a tale that these people, well, they may have been Nazi perpetrators, but they were also victims. Horst also hangs on to the poisoning theory because it turns his father into a victim.

After the book comes out, a guy in Jerusalem writes to me about his father-in-law, an Italian Jew who was one of the early recruits to what becomes Mossad and in 1948 is sent back to Italy to hunt Nazis. For the first time, now we have confirmation that there was a group of four Jewish guys from Palestine who have flown into Rome to track what Otto was up to. And this has reopened my investigation.

Horst and you have been in this relationship in which he tries to convince you of his father’s goodness and you keep presenting evidence of his war crimes. Does he think if he keeps at it long enough, you’ll come around?

I tried to persuade him and he tried to persuade me. We both failed miserably. I would say, I don’t think it’s about his relationship with his father. I think it’s about his relationship with his mother. He really loved his mother, who in my view was as ghastly as the father. And she bequeathed to him the task of protecting the family name. It’s about constructing a sort of more sanitized acceptable version of the family history.

While we were making the film, [English director] David Evans and I were pretty anxious about the state of Horst’s emotional well-being. We retained the services of a psychiatrist and a psychoanalyst, and at one point the psychoanalyst said to me, “Horst is like his castle. The walls seem impregnable, and strong enough to last another 1,000 years. But the moment you step inside the building, you can see that the whole thing is on the verge of collapse.”

I think he’s constructed a narrative that allows him to get through each day, and the more I try to undermine the foundation, the more he’s got to build it up.

Philippe Sands participates in a panel discussion during a ceremony marking the 75th anniversary of the start of the Nuremberg war crimes trials in Germany, Nov. 20, 2020. (Daniel Karmann/Pool/AFP via Getty Images)

How did he react to “The Ratline”?

There have been some dramatic consequences as a result of the last line in the book, which is spoken by his daughter Magdalena: “My grandfather was a mass murderer.” And he’s disinherited her, his only child.

In your day job as a lawyer you adjudicate human rights abuses and war crimes. What are the lessons that you take away from the period during and especially after World War II?

Before COVID I’d done work in Africa, Asia, Bangladesh, Ghana, Mexico, Argentina and Chile. And the central theme is really family secrets, keeping things locked away, and how they then reemerge and cause mayhem later. That is a universal thing. Like Ahn Sang Suh Kyi: Why is this icon of human rights, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, defending what the Myanmar military has done against the Rohingya? And it just came to me that it’s really all about her father, that her father was the founder of the Myanmar Armed Forces. Every mass atrocity is unique, but it’s the points of commonality that are more striking than the points of difference.

Are you done with this story? Do you want to move on?

I do want to move on. My wife wants me to move on. But it will end up being a trilogy. The third one takes us to South America and a minor character in “The Ratline” called Walter Rauff, an SS officer who was Otto’s colleague and comrade. In 1956 he moves to Chile, where he becomes a businessman in Punta Arenas. When Pinochet takes over, Rauff became an interrogator and torturer for the intelligence services. In October 1998 I learned that Pinochet’s lawyers had been onto me; they wanted me to act for him in his case, defending him against crimes against humanity and genocide. Amazingly, that’s what he was indicted for. And my wife told me, “If you [defend] Pinochet, I will divorce you tomorrow.”

These things go on and on and on: Unbelievably, in the summer of 1945, Rauff is being hunted by a young naturalized American counterintelligence agent named Henry Kissinger, who just 28 years later will be on the side of Pinochet’s team. Life is very strange.