7 new books about the Holocaust you should read, according to scholars

Published April 14, 2017

Jewish studies scholars recommended these seven recently published books about the Holocaust. (JTA collage; background image: Piotr Drabik/Wikimedia Commons)

(JTA) — From Anne Frank’s diary to Elie Wiesel’s “Night,” books about the Holocaust remain some of the most powerful and well-known pieces of literature published in the past century. Books have the power to educate about the Shoah’s unimaginable horrors and bring to life the stories of its victims, as well as unearth hidden details about wartime crimes.

Ahead of Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Memorial Day, JTA reached out to Jewish studies scholars across the country seeking their recommendations on recently published books dealing with the Holocaust. Their picks, all published in the past three years, include an investigation into the 1941 massacre of Jews in the Polish town of Jedwabne (two scholars recommended the same book on that topic), a critical examination of theories trying to explain the Holocaust and a look at how Adolf Hitler saw Islam as a religion that could be exploited for anti-Semitic purposes.

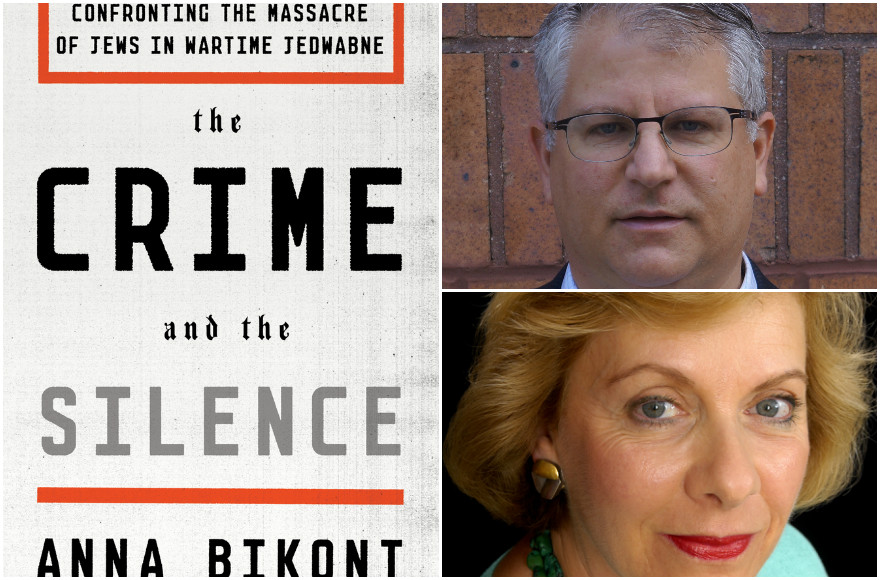

“The Crime and the Silence: Confronting the Massacre of Jews in Wartime Jedwabne,” by Anna Bikont (Courtesy of Farrar, Straus and Giroux); Joshua Zimmerman (Courtesy of Zimmerman); Barbara Grosman (Courtesy of Grosman)

The Crime and the Silence: Confronting the Massacre of Jews in Wartime Jedwabne (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015)

By Anna Bikont

Joshua Zimmerman, professorial chair in Holocaust studies and East European Jewish history, and associate professor of history at Yeshiva University, writes:

This book, a winner of the 2015 National Jewish Book Award, was written by a Polish journalist who discovered she was Jewish in her 30s and became deeply engaged in the topic of Polish-Jewish relations. After Jan T. Gross’ controversial book “Neighbors: the Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland” (2000) proved that the local Poles — not the Germans — committed the massive pogrom in that town in July 1941, Bikont went to Jedwabne and its surroundings, interviewing eyewitnesses to the crime in the years 2000 to 2003, shedding new light on the character of the perpetrators, bystanders and the intricate way the crime was concealed for 50 years after the Holocaust. It is written in the form of a journal of the author’s travels and conversations with people.

Barbara Grosman, professor of drama at Tufts University and former U.S. Holocaust Memorial Council board member, also recommended Bikont’s book. She writes:

I first read about the Jedwabne massacre in Gross’ book and still remember being riveted by the cover image of a barn engulfed in flames. Perhaps because my paternal grandfather was from Łomża, Poland — a city relatively near Jedwabne — I felt a particular connection to this atrocity, as well as gratitude to him for leaving the country years before the Holocaust. I directed Tadeusz Słobodzianek’s “Our Class,” a play loosely based on the events in Jedwabne, at Tufts in 2012, and remain fascinated by this story of greed, treachery and cruelty, a horrific crime in which as many as 1,600 Jewish men, women and children perished. Bikont’s magnificent work of investigative journalism details her meticulous reconstruction of the massacre and its subsequent decades-long coverup. It is a sobering and compelling account of anti-Semitism, denial and isolated acts of heroism.

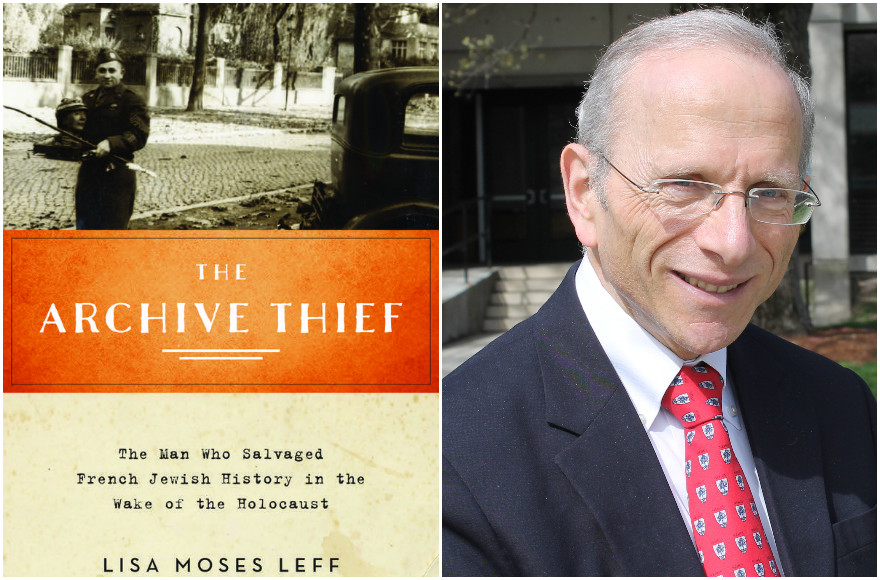

“The Archive Thief: The Man Who Salvaged French Jewish History in the Wake of the Holocaust,” by Lisa Moses Leff (Courtesy of Oxford University Press); Jonathan Sarna (Uriel Heilman)

The Archive Thief: The Man Who Salvaged French Jewish History in the Wake of the Holocaust (Oxford University Press, 2015)

By Lisa Moses Leff

Jonathan Sarna, professor of American Jewish history at Brandeis University, writes:

This award-winning book recounts the amazing story of Zosa Szajkowski, the scholar who rescued archives that might otherwise have been lost in the Holocaust. Szajkowski wrote numerous books and articles, but was also a known archive thief, caught red handed stealing valuable papers from the New York Public Library. Leff’s meticulous account reads like a thriller, yet conveys invaluable information concerning the fate of Jewish archives during and after the Shoah, and why removal of archives from their original home matters. Brandeis University and my late father, Bible scholar Nahum Sarna, play bit parts in this story. I remember Szajkowski, too; in fact, I took a class with him as a Brandeis undergraduate. He told lots of stories in class about his archival experiences during and after World War II, but it was only after reading Leff’s wonderful book that I understood “the rest of the story.”

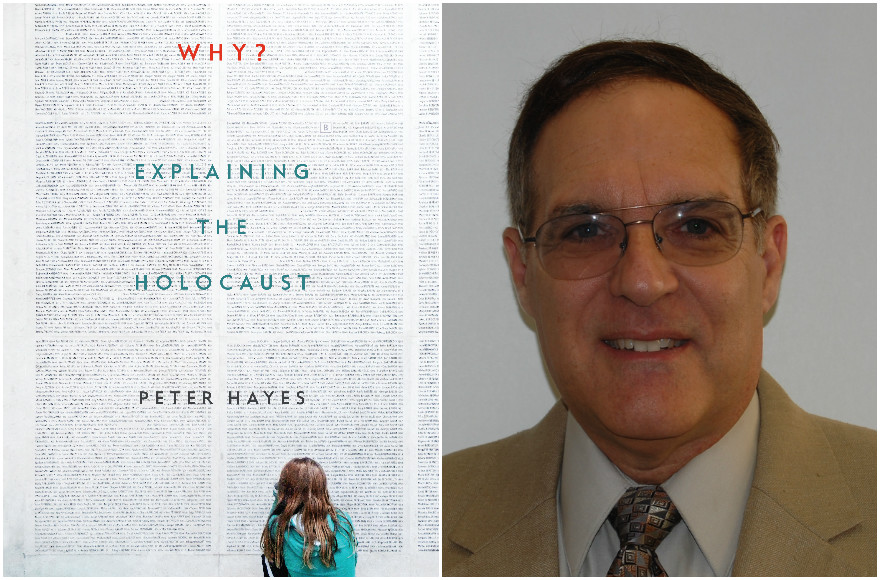

“Why? Explaining the Holocaust,” by Peter Hayes (Courtesy of W.W. Norton & Company); David Engel (Courtesy of Engel)

Why? Explaining the Holocaust (W.W. Norton & Company, 2017)

By Peter Hayes

David Engel, professor of Holocaust studies and chair of Hebrew and Judaic studies at New York University, writes:

I recommend this book for a lucid, well-crafted introduction to the history of the Holocaust. Unlike most works on the Holocaust written for a general audience, which tend to emphasize how the Holocaust was carried out and experienced, Hayes’ book concentrates, as its title suggests, on helping readers to understand why the Holocaust occurred when it did, where it did, in the manner it did and with the results it produced. It offers readers a window onto how historians go about finding answers to these questions, why some answers turn out to be more compelling than others and how new evidence can change understanding.

“Probing the Ethics of Holocaust Culture, by Claudio Fogu, Wulf Kansteiner and Todd Presner (eds.) (Courtesy of Harvard University Press); Omer Bartov (Courtesy of Bartov)

Probing the Ethics of Holocaust Culture (Harvard University Press, 2016)

Edited by Claudio Fogu, Wulf Kansteiner and Todd Presner

Omer Bartov, professor of European history and German studies at Brown University, writes:

This book comes out a quarter of a century after the publication of Saul Friedlander’s crucial edited volume, “Probing the Limits of Representation: Nazism and the Final Solution” (1992), which had challenged the conventional discourse on the mass murder of the Jews and critiqued its popular representation. The current volume attempts to grapple with the wider impact of Holocaust scholarship, fiction and representation in the intervening period. It includes fascinating essays on new modes of narrating the Shoah, the insights provided by the “spatial turn” on research and understanding of the event and the politics of exceptionality, especially the contextualization of the Holocaust within the larger framework of modern genocide. As such, it enables readers to understand both the ongoing presence of the Holocaust in our present culture and the different ways in which it has come to be understood in the early 21st century.

“Islam and Nazi Germany’s War,” by David Motadel (Courtesy of Belknap Press); Susannah Heschel (Courtesy of Heschel)

Islam and Nazi Germany’s War (Belknap Press, 2014)

Susannah Heschel, professor of Jewish studies at Dartmouth College, writes:

This is a major work of scholarship, examining the various ways the Nazis fostered a relationship with Muslims both before the war and especially during the war. Jeffrey Herf wrote a book a bit earlier, “Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World,” detailing Nazi anti-Semitic propaganda sent, in Arabic translation, to North African Muslims, and Motadel expands the range of influence: that Hitler understood Islam as a warrior religion that could be exploited for propaganda efforts and to serve in both the Wehrmacht and the SS. The indoctrination of Muslims with Nazi anti-Semitic propaganda may well have had effects lasting long past the end of the war, a topic that deserves additional attention.

“My Grandfather Would Have Shot Me: A Black Woman Discovers Her Family’s Nazi Past,” by Jennifer Teege and Nikola Sellmair (Courtesy of The Experiment); Michael Rothberg (Courtesy of Rothberg)

My Grandfather Would Have Shot Me: A Black Woman Discovers Her Family’s Nazi Past (The Experiment, 2015)

By Jennifer Teege and Nikola Sellmair

Michael Rothberg, professor of English and comparative literature and chair in Holocaust studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, writes:

Teege’s memoir, published in German in 2013 and translated into English in 2015, is a fascinating contribution to the discussion of the ongoing impact of the Holocaust over multiple generations. When she was in her late 30s, Teege discovered that her grandfather was a Nazi war criminal. And not just any Nazi: he was Amon Goeth, the commandant of Plaszów depicted in the film “Schindler’s List.” Because Teege is herself a black German woman — the daughter of a Nigerian father and a white German mother who was herself the daughter of Goeth’s mistress — her story takes on additional resonance. Intercut with contextualizing passages by Sellmair, a journalist, Teege’s memoir both confronts historical conundrums about race, reconciliation and responsibility for the past, and offers glimpses of very contemporary questions about the contours of German identity. Her earnest reckoning with family and national history can inspire us all to reflect on what it means to be implicated in histories of racial violence, even those we have not participated in directly.

“They Were Like Family to Me: Stories,” by Helen Maryles Shankman (Courtesy of Simon & Schuster); Jeremy Dauber (Courtesy of Dauber)

They Were Like Family to Me: Stories (Scribner, 2016)

By Helen Maryles Shankman

Jeremy Dauber, director of the Institute for Israel and Jewish Studies and professor of Yiddish at Columbia University, writes:

Writing literature about the Holocaust is many things, but it is never easy; and writing Holocaust literature in the vein of magic realism is more difficult yet. It risks taking the great horror of the 20th century and rendering it ungrounded, imaginative, even — God forbid — whimsically slight. But when a skillful writer pulls it off — David Grossman, for example, and now Shankman — the fantastic casts illuminating and terrible light on the dark shadows of the history of the war against the Jews. The stories in her collection are by no means factual in all respects. But they contain unmistakable truth.