When Jewish students in America raised alarms about the Holocaust

Published May 7, 2018

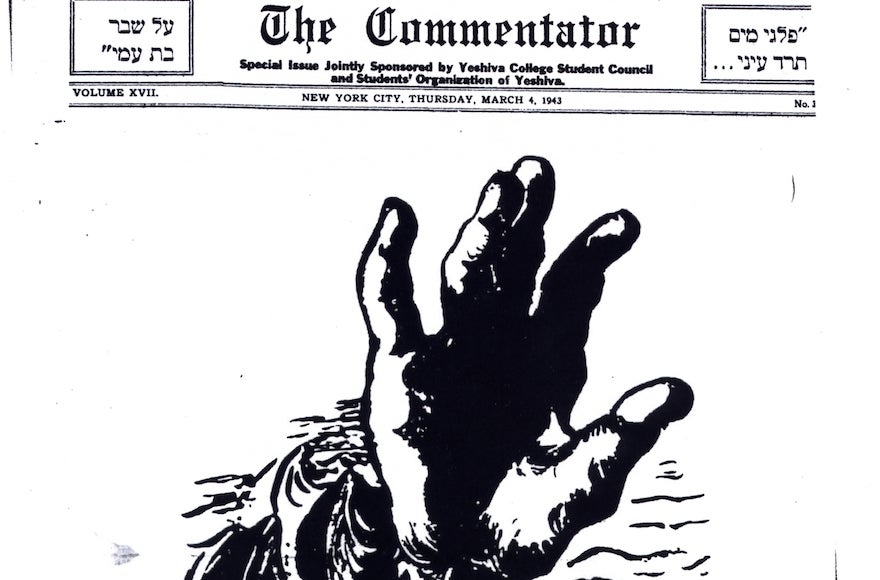

The cover of Yeshiva University’s student newspaper, The Commentator, from March 4, 1943, shows that Jewish students were active in efforts to draw attention to the plight of Europe’s Jews. (Courtesy of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies)

JERUSALEM (JTA) — Seventy-five years ago this month, a handful of rabbinical students in New York City helped mobilize hundreds of churches and synagogues nationwide to cry out against the Nazis’ mass murder of European Jewry.

That remarkable interfaith protest is omitted from the U.S. Holocaust Museum’s new exhibit on “Americans and the Holocaust,” which explores how much Americans knew about the Nazi persecution of the Jews and how early they knew it. The students’ actions were a significant part of that story and deserve to be told.

Our fathers, the late Noah Golinkin and Buddy Sachs, together with their friend Jerome Lipnick, were students at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America in late 1942 when news about the slaughter of Europe’s Jews was publicly confirmed by the Allies. The students were shocked — not only by the news of the mass killings, but by the refusal of the Roosevelt administration to do anything beyond verbally condemn the Nazis and the timidity of ultra-cautious American Jewish leaders.

So the JTS students took matters into their own hands. They organized an extraordinary Jewish-Christian interseminary conference in February 1943 to raise public awareness about the Holocaust. Hundreds of students and faculty from 13 Christian and Jewish seminaries attended, with sessions alternating between JTS and its Protestant counterpart, the nearby Union Theological Seminary. The speakers and panel participants included prominent Jewish and Christian leaders along with an array of refugee and relief experts.

The conference was an important first step, but the students didn’t stop there. Next they turned to the Synagogue Council of America, the national umbrella group for Orthodox, Conservative and Reform synagogues. At the students’ behest, the council launched a seven-week publicity campaign to coincide with the traditional period of semi-mourning between Passover and Shavuot.

An interseminary conference of theological students to consider plans for the rescue of European Jewry was held at the Union Theological Seminary and the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, Feb. 22, 1943. (Courtesy of The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies)

Seventy-five years ago this month, synagogues throughout the country adopted the committee’s proposals to recite special prayers for European Jewry; limit their “occasions of amusement”; observe partial fast days and moments of silence; and write letters to political officials and Christian religious leaders.

They also held memorial protest rallies, at which congregants wore black armbands designed by Golinkin — three decades before Vietnam War protesters would adopt a similar badge of mourning.

These rallies held on May 2, 1943, in many instances were led jointly led by Reform, Conservative and Orthodox rabbis — an uncommon display of unity. Equally significant, the Federal Council of Churches, whose foreign secretary had addressed the students’ interseminary conference earlier that year, agreed to organize memorial assemblies at churches in numerous cities on the same day.

Many of the assemblies featured speeches by both rabbis and Christian clergymen, as well as prominent political figures. Prayer services and rallies were held across the United States in cities such as New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Hartford, Providence, Chattanooga and Kansas City, as well as in the state of Nebraska.

The gatherings received significant coverage in newspapers and on radio. “Milwaukee Churches Call on U.S., Allies to Open Doors to Refugees,” one headline read. “Nazi Barbarism Condemned by Pastor at Temple Service,” another declared.

This important Jewish-Christian alliance helped raise American public awareness about the Nazi slaughter of European Jewry, and increased the interest of Congress and the media in the possibility of rescuing Jews from Hitler — which, in turn, turned up the pressure on the White House to take action.

At a time when the prevailing assumption was that nobody cared and nothing could be done to save Jews from Hitler, three rabbinical students managed to mobilize Christian sympathy for Hitler’s victims and convince a major Jewish organization to undertake a nationwide protest campaign.

Last year, when staffers at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum began designing “Americans and the Holocaust,” Holocaust historian Dr. Rafael Medoff and David Golinkin met with two senior museum officials. We presented them with a copy of the book we co-authored, “The Student Struggle Against the Holocaust.” We explained the significance of the students’ actions. In the months to follow, we reiterated those points in correspondence with the exhibit curators. Actually the staffers already had all the documentation in their own files before we approached them.

We were surprised and saddened to discover this week that the interfaith protest campaign by synagogues and churches throughout the United States in the spring of 1943 is not mentioned in the exhibit. Likewise, there is no mention of the remarkable conference of Christian and Jewish seminary students. One article that our fathers wrote is buried in an interactive display about media coverage of the Holocaust — and there is no mention of the conference or the campaign.

Obviously we felt it is important to honor our fathers (in keeping with the fourth of the Ten Commandments), but the issue has broader significance, which is why we are publishing this article. These student protests by clergy are a vital chapter in the history of American responses to the Holocaust because they were forerunners of the mass interfaith protests by students and clergy for human rights and human lives since the 1960s that shook American politics then, but failed to do so in the 1940s.

The running theme of the U.S. Holocaust Museum’s new exhibit is that anti-Semitism and anti-immigrant sentiment were extremely strong among the American public in those days. That point comfortably fits the exhibit’s argument that it was impossible for FDR to do very much to help Jewish refugees.

But sometimes history is not so black and white. While there were many bigots in those days, there were many good people, too. While many Jews were afraid to protest against an otherwise friendly administration at the time, our fathers showed something bolder could still be envisioned and attempted when they helped mobilize thousands of good people, of all faiths, to speak out. That is an important part of the story, and it should have been included in this major new exhibit.

Rabbi David Golinkin is president of the Schechter Institutes, Inc., Jerusalem. Noam Sachs Zion is a senior researcher at the Shalom Hartman Institute, Jerusalem.