Seeking Kin: Son looks for the father he never knew

Published October 10, 2013

Yehuda Cohen’s Israeli identification card is about the only personal item Herve Cohen has of his father. (Courtesy Herve Cohen)

The “Seeking Kin” column aims to help reunite long-lost relatives and friends.

BALTIMORE (JTA) – The official Israeli identification card in Herve Cohen’s hand is about the only evidence he has of his father’s existence.

Cohen, who lives near Paris in Issy les Moulineaux, decided a few years ago to try to find his father, Yehuda. At 33, Cohen is a little young to remember meeting him, since his parents were divorced in 1982 and his father’s trail disappeared by 1990.

A few years ago, Cohen began learning what he could from his mother, Goelle Beros. He traveled to Israel to meet Yehuda’s sisters, Rachel Kigler and Sarah Birenbaum, and brother Bernard. He’s spoken with Shalom Polzilov, a Jerusalemite who in the late 1980s knew Yehuda in Brooklyn, N.Y.

No one has a clue as to where Yehuda is. His sisters last heard from him 23 years ago; they fear the worst.

“I want to find my father because if he is dead — I am religious — I can say Kaddish,” Cohen said, referring to the prayer recited by mourners on the anniversary of a relative’s death. Beyond that, said Cohen, an information systems engineer, knowing his father’s fate would offer “equilibrium and stability.”

The reality, he explains, is “very complicated.”

Yehuda and Goelle, who went by her Hebrew name, Yael, met in Israel in the 1970s. Yael had made aliyah from France and was living in Arad, where Yehuda had moved from the northern coastal city of Acre. They married in Arad and in 1977 had a son, Amitai. In 1979, Yael became pregnant with Herve. Yael apparently told Yehuda she preferred giving birth in France, so she flew ahead with Amitai and moved in with her parents in the northern town of Tracy le Mont.

Yael, according to Kigler and Birenbaum, refused to return to Israel. Yehuda moved to northern France, but Yael’s parents kept him away. The couple divorced in 1982, and Yehuda relocated to Paris, where he worked as a security guard at a Jewish school, Ohr Yosef. Yael soon remarried a non-Jewish man, Francis Podevin, whom Herve considers “my French father.”

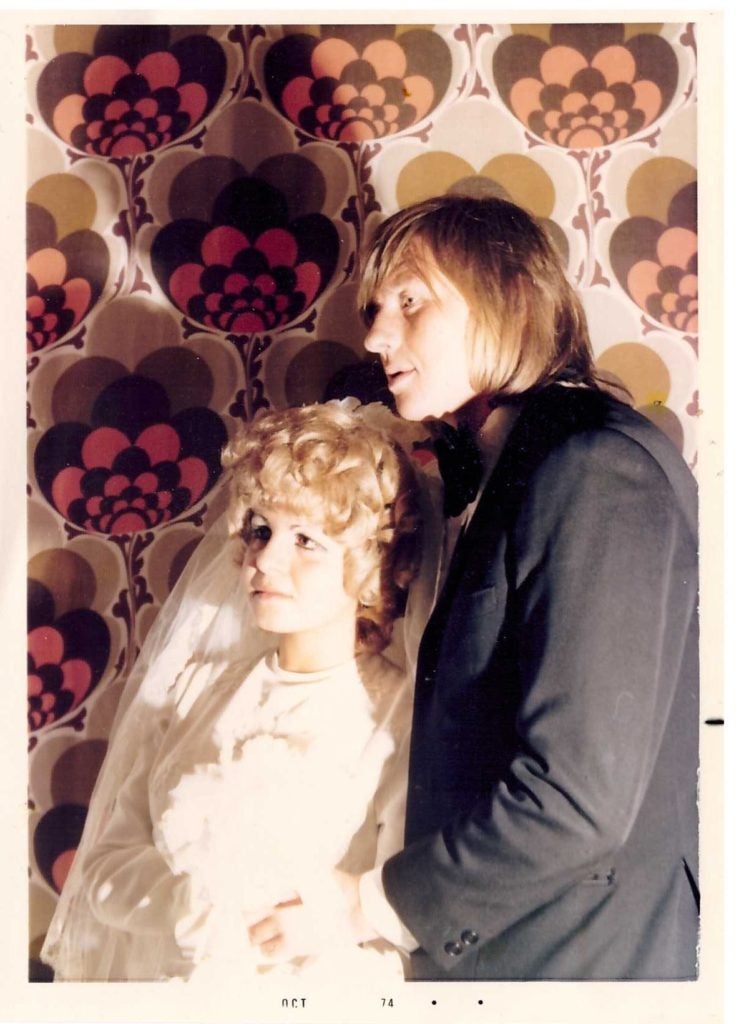

Yehuda Cohen, shown with his wife, Yael, at their wedding in Israel, has not been heard from since 1990. (Courtesy Sarah Birenbaum)

Part of the reason for that, he said, was Yehuda’s absence, which Herve doesn’t understand. According to what Herve learned from Yael, Yehuda was wanted by French authorities for counterfeiting or forgery, and may have been arrested. Herve also heard that Yehuda’s friends in the Paris Jewish community bought him a plane ticket to New York, and Yehuda soon moved there – and according to one version, became observant. Someone else told Cohen that his father may have been killed. Yet another person said he had planned to move to Germany with a woman.

The truth is hard to ascertain because Yehuda apparently entered and worked in France and the United States illegally, so his sisters and son believe he likely kept a low profile and didn’t leave much of a paper trail.

Herve doesn’t know what to believe.

“There are so many versions, I’m not sure,” he said. “This is a mystery.”

Herve and Yehuda’s sisters said that for many years, Yehuda was involved in gambling and drugs. Birenbaum, who said she and her brother were once very close, traced his problems to when he and their parents, Shmuel and Netti, moved in 1962 to Israel from their native Iasi, Rumania. Yehuda, then 14, “had a hard time adjusting” to his new surroundings. He rarely attended school in Israel, fell in with a bad crowd, stole and used drugs, she said.

“I was embarrassed that he was my brother,” said Birenbaum, a retired optician and, at 62, two years Yehuda’s junior. “When I saw him on a corner, I’d cross the street so he wouldn’t see me.”

Whether because of the asthma he apparently acquired in Acre or in search of a fresh start, Yehuda moved to Arad at about age 20. Shmuel tried to get his son established, so he took out a mortgage on a storefront for a prospective coffee shop. But Yehuda never launched the business, instead working at odd jobs.

What Yehuda did the rest of his life, no one is quite sure. Polzilov, who attended the Lubavitch yeshiva in Brooklyn’s Crown Heights neighborhood from 1985 to 1988, remembers Yehuda working at a food store and cleaning buildings, but not for very long. Yehuda then lived with two or three roommates in an apartment on Union Street or President Street and often ate his meals at the nearby yeshiva, Pozilov said.

“Yehuda and I would meet at the dining room” of the yeshiva, Polzilov said. Yehuda “didn’t look healthy,” but Polzilov said he never pried regarding personal matters. By chance, Polzilov knew Kigler and her husband, Avraham, as neighbors in Jerusalem, so when he returned to Israel during school breaks, he told them he saw Yehuda occasionally.

When Yehuda lived in Paris, the Kiglers once visited the city. Kigler remembers her brother’s dropping by the couple’s hotel and bringing them a camera as a gift. But they didn’t see much of each other on that trip.

She and Birenbaum last heard from him in 1990, when Shmuel died and the sisters sent Yehuda about $500. Before that, he’d occasionally telephone Birenbaum, usually in the middle of the night, Israel time, and always, he said, from a friend’s house. Birenbaum would ask for his telephone number and address, but always was rebuffed.

Now she lacks even such clues to attempt a search.

“Something must have happened to him,” she said. “It’s very sad. For so many years, we’ve heard nothing from him.”

(Please email Hillel Kuttler at [email protected] if you would like “Seeking Kin” to write about your search for long-lost relatives and friends. Please include the principal facts and your contact information in a brief email. “Seeking Kin” is sponsored by Bryna Shuchat and Joshua Landes and family in loving memory of their mother and grandmother, Miriam Shuchat, a lifelong uniter of the Jewish people.)

![]()