The Background: Post-Holocaust Polish Repatriation

From the start of the Bolsheviks’ war on religion, the Sixth Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak, led the Jewish resistance. For this work, he was arrested in the summer of 1927 and initially condemned to death. His sentence was first commuted to 10 years of hard labor, then three years of exile, and finally, on the 12-13 of the Jewish month of Tammuz, full release. In October of 1927, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak was forced to leave the Soviet Union “but not before he had trained many teachers whose influence was felt in the USSR long after his departure.”4 Through the absolute hell of the 1930s, Lubavitcher Chassidim continued to risk their lives to maintain Jewish life and learning in the Soviet Union, as they’d been charged by the Sixth Rebbe. Many, including Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson—father of the Seventh Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, of righteous memory, and until his 1939 arrest the chief rabbi of Dnepropetrovsk, Ukraine—paid the ultimate price.

ADVERTISEMENT

With the outbreak of World War II, a sizable portion of the Chabad-Lubavitch community escaped the German onslaught and local collaborators’ zeal by evacuating to Tashkent and Samarkand, in Soviet Uzbekistan. There, joined by tens of thousands of Jewish refugees from the USSR and Poland, they recreated Jewish life, opening yeshivahs, building mikvahs and praying together in synagogue. The Lubavitcher Chassidim did not just care for themselves but actively recruited Jewish children to study Torah, many for the first time in their lives. The children, who were cared for materially as well, drew from the widest background, including Bukharian locals, Polish refugees and members of the Soviet nomenklatura. Among their students was even a 16-year-old relative of Stalin acolyte Lazar Kaganovich.6 This is how the memo to Abakumov describes this period: “According to SCHNEERSON’s directives, the Chassidim intensified their anti-Soviet activities and created illegal schools in the cities of Samarkand and Tashkent, in which Jewish youth who fell under their influence studied in a religious and nationalist spirit.”

The war years in Uzbekistan were by no means easy, with the secret police continuing to operate, and adults and children dying from privation and diseases. Nevertheless, this was a relative period of peace for the beleaguered Chassidim of the USSR. With the end of World War II, however, it became clear that this situation would not last for much longer. That’s when a rare opportunity to escape the Soviet Union first presented itself.

Just a few months after the war, on July 6, 1945, the Soviet Union signed a treaty with the Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland agreeing on a population exchange. Ethnic Russians, Ukrainians, Belorussians and Lithuanians would have their Polish citizenship exchanged for a Soviet one, while ethnic Poles and Polish Jews who now found themselves in the Soviet Union would be repatriated to Poland. “A secret instruction of December 1945 specified that Poles and Jews (i.e., not Ukrainians and Belorussians) who had lived on the territory of Poland up to September 17, 1939, might return from the USSR.”7 This meant that even eligible individuals who’d formerly been residents of the eastern half of Poland, which in the aftermath of the Hitler-Stalin non-aggression pact had been annexed by the Soviet Union (and to this day is a part of Belarus), could renounce their unilaterally granted Soviet citizenship and return “home” to Poland.

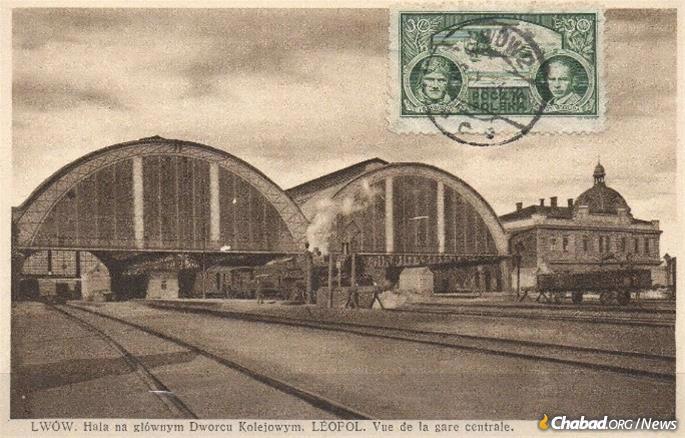

Special joint Polish-Soviet committees were established to facilitate this repatriation, and as 1946 progressed, ever larger numbers of people were granted permission to leave. Many traveled to Poland in separate cars attached to regularly scheduled trains. Albert Kaganovitch estimates that over the duration of 1946 about 147,000 Jews were allowed to leave the USSR in this way. This might appear generous on Stalin’s part, but the truth was the Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland, formerly called the Lublin Committee, was a pro-Soviet puppet entity that Stalin was using to outflank the Polish government-in-exile in his plan to transform post-war Poland into a Communist satellite state. Whatever Stalin’s reasons were for allowing Jews out, the fact remains that Polish repatriation presented a limited window of opportunity to leave the Soviet Union.

The Lubavitchers in Central Asia and other places of evacuation throughout the Soviet Union had for the duration of the war lived side by side with Polish Jewish refugees. Now the Polish Jews were heading to Lvov to be repatriated back to Poland, from which they could go on to Mandatory Palestine, the United States or other countries in the West. As Soviet citizens, the Lubavitcher Chassidim were ineligible to leave, but by the end of 1945 the idea of somehow taking advantage of this window was percolating.9