What’s it like being a Nazi hunter?

Published February 12, 2023

This story is published here in partnership with the National Library of Israel.

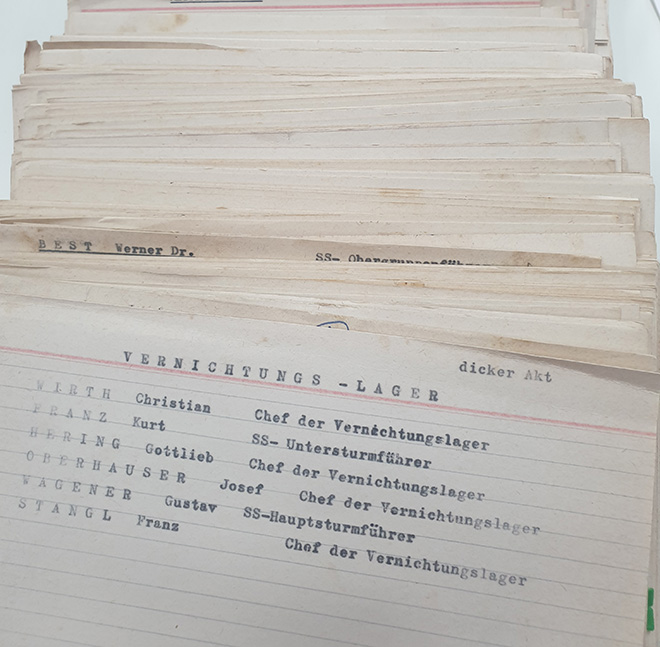

Imagine a typical workday that went something like this: you wake up, drink your morning coffee, and leaf through the local newspaper. Then you shower, dress and head to the office where you find stacks of mail on your desk from all over the world. You read the European newspapers, open the letters, and arrange all the information you have gathered in an index-card file arranged alphabetically, which looks something like this:

ADVERTISEMENT

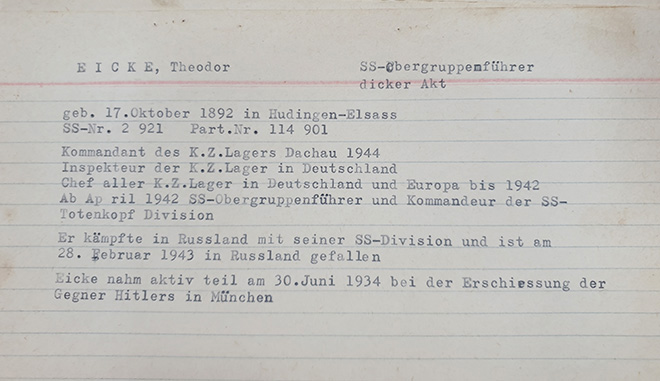

Of course, back then the cards were either stored in a rotating desktop card index, called a rolodex, or perhaps filed in drawers in a fancy mahogany wood filing cabinet. But all that is less important – You lean back in your chair, smoke your pipe if you like, and go over the text on the cards once more. You open up the personal files, look over the photos and biographical details, and try to verify the information you’ve received. All this as part of the effort to discover the current whereabouts of these people—the individuals responsible for what is likely the greatest crime in human history.

|RELATED: Nazi-era ‘resistance fighter’ exposed as concentration camp guard

This was the life of Tuviah Friedman (sometimes spelled Toviyya), whose business card could have featured the simple job description: “Nazi Hunter”. In the 1950s, gathering information was a much harder task than it is today – no Google, no Facebook. But Friedman set himself one mission with a single objective: find and prosecute as many Nazi war criminals as possible.

His quest to catch Nazis began even before the war was officially over. When the Russian army entered Friedman’s hometown, Radom, in Poland, the new occupiers sought to reorganize the local police and Friedman took advantage of the opportunity, enlisting under a false identity. As part of his job, he exposed, arrested, and brought Nazi criminals to justice.

At some point, Friedman concluded that his future was not in Poland. He quit the police and decided to immigrate to Mandatory Palestine. Leaving what was then communist Poland through illegal means, he arrived in Vienna on his way to Palestine, but then, his plans changed.

In Vienna, he met members of the Haganah involved in the clandestine immigration of Jewish refugees to the Land of Israel (they belonged to the Haganah’s Mossad LeAliyah Bet organization). These operatives suggested that Friedman form a team to track down Nazi war criminals, which is exactly what he did. Friedman settled in the Austrian capital and began gathering information, and with the help of the Vienna police, he was not only able to locate SS officers in hiding, but also to bring forth evidence that helped in their arrest, and sometimes even their prosecution.

ADVERTISEMENT

Back then, how would one go about bringing Nazi criminals to justice? First, one would have to create a separate file for each Nazi, including their name, date and place of birth, rank and position in the German army, SS, Gestapo or Nazi Party. Next, one would have to find evidence and proof of that individual’s part in crimes against humanity. Then of course there was the need to physically locate the fugitives—find out where they were living, whether they had changed their identity and if so, all the details of their new identity, including any new names or aliases and whether they had changed their appearance.

Finally, one had to convince the authorities to act on the evidence and materials that had been collected. Friedman did all of this. For his files on suspected Nazis, he would track down photos and news articles or other information that would indicate their responsibility for the crimes committed personally by them or under their direction. In this way, he was able to capture SS officers who had ordered the extermination of the Jews of Radom. During his time in Austria, he managed to bring about the arrest of some 250 Nazis.

One of these was Kurt Becher, who served as head of the SS Economic Department in occupied Hungary as well as commissar of all German concentration camps. Becher is particularly known for his negotiations with Rudolf Israel Kastner which facilitated the escape of some Budapest Jews to Switzerland in exchange for goods and money. Kastner testified as a character witness on Becher’s behalf after the war and the former Nazi officer was eventually released. He would go on to become a successful businessman despite his criminal past documented by Friedman and others.

Friedman’s Nazi files contain details about many more Nazis: Theodor Eicke, commandant of the Dachau concentration camp; Hans Bothmann, commandant of the Chelmno extermination camp; Bruno Streckenbach, a senior officer in the Reich Security Ministry who was placed in charge of operations of the Einsatzgruppen. These are just a few examples from the hundreds of index cards on Friedman’s rolodex of Nazis.

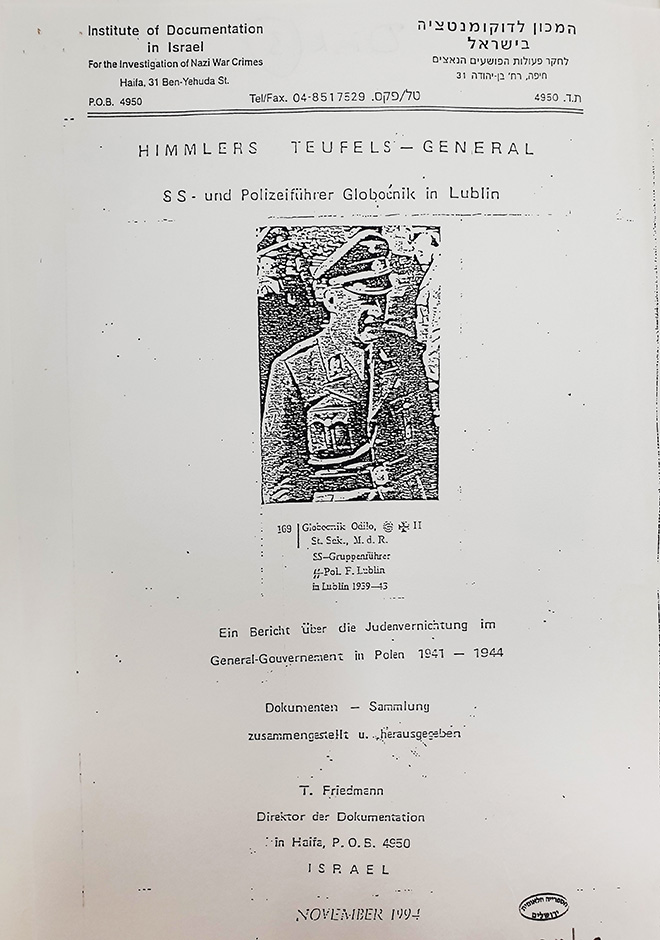

In 1952, Friedman finally immigrated to Israel, and after working for a period at Yad Vashem, he moved to Haifa, where he re-established the organization he had founded in Vienna, now called the Institute for the Documentation of Nazi War Crimes. Friedman was critical of Yad Vashem’s focus on documenting the victims and survivors of the Holocaust instead of actively searching for the Nazi criminals responsible.

Indeed, the documents at the Institute for Documentation are a kind of mirror image of the Yad Vashem archives. Instead of lists of those who perished, there are rosters of Nazis with information on their various roles and documentation of their actions during the Holocaust.

In Haifa, he continued his work to locate the same Nazi criminals, but with fewer resources and less assistance than he had in Austria. He built up his files on Nazi officers of different ranks, from camp commandants like Rudolf Höss, who was in charge of Auschwitz, to the most senior Nazis like Hermann Göring, commander of the Luftwaffe. Friedman mainly devoted his time to raising media awareness of the need to bring members of the Nazi regime to justice and maintaining public interest in their capture even when the country’s attention had turned elsewhere.

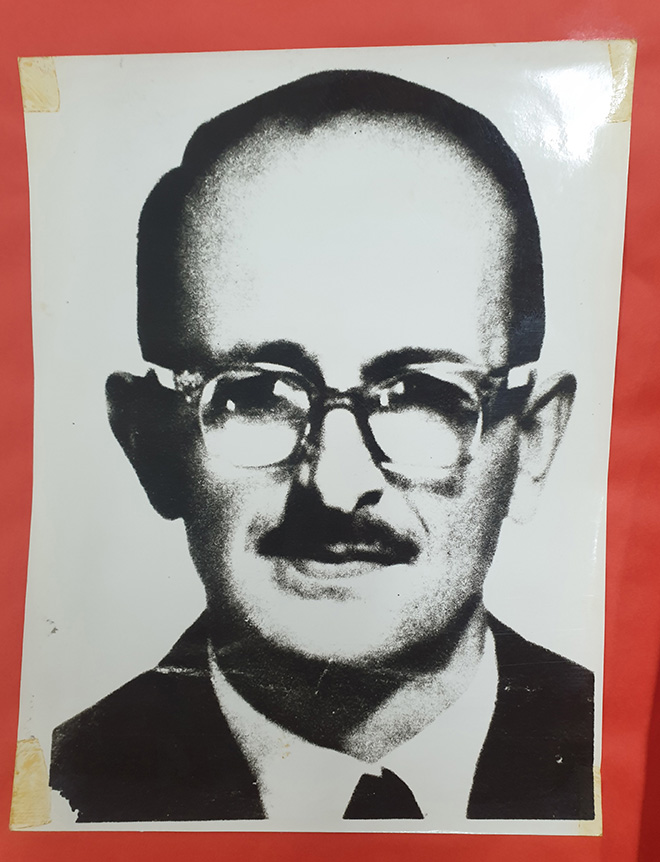

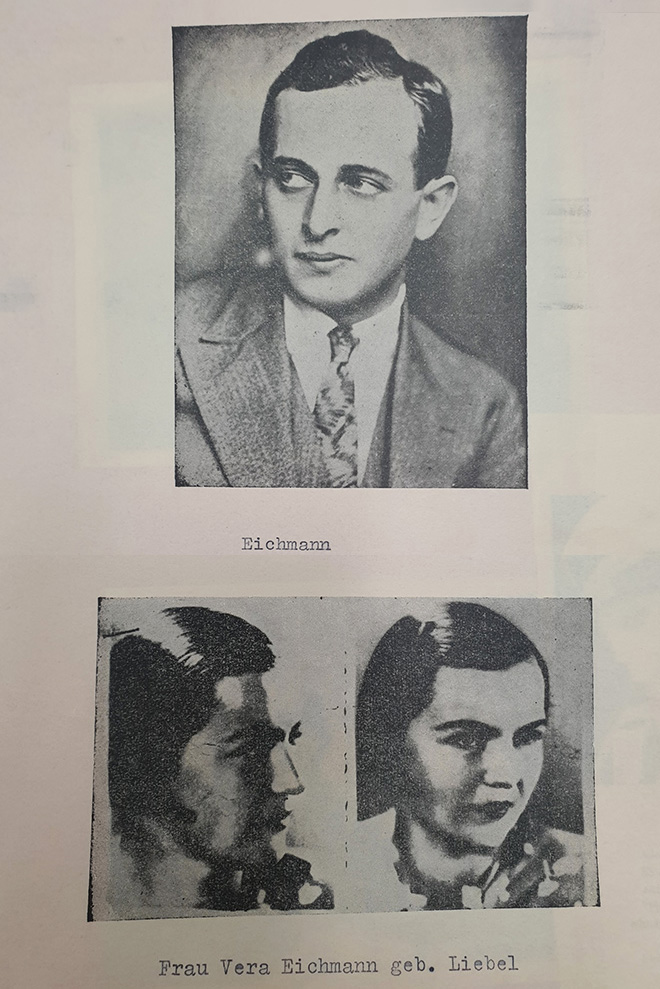

The highlight of Friedman’s life’s work was undoubtedly his contribution to the capture and prosecution in Israel of Adolf Eichmann. Friedman had begun gathering information about Eichmann, the Nazi officer responsible for implementing the Final Solution, during his Vienna days, and had even obtained an up-to-date photo of him. A number of rare photos of Eichmann are preserved in Friedman’s archive, which can be seen here.

He continued to collect information from around the world about Eichmann’s current hiding place and used the media to lobby for his capture. He even offered a cash reward for information about Eichmann, after which he began to receive letters from people claiming to know his whereabouts. Friedman was the first to receive a tip that Eichmann was living in Argentina, which he passed on to the Mossad. It was Friedman who convinced the Mossad to actively pursue Eichmann’s capture.

After Eichmann’s capture, Friedman sent the file he had amassed for over 15 years on the Nazi officer to the Israel Police, and directly assisted in building the legal case against him. The Eichmann case is certainly the most famous of Tuviah Friedman’s Nazi hunting stories. Tuviah Friedman’s archive is preserved in the National Library of Israel. Its contents, which show his methodical and painstaking work, are available for viewing here.