Joan Nathan cookbook brings families together

Published November 30, 2015

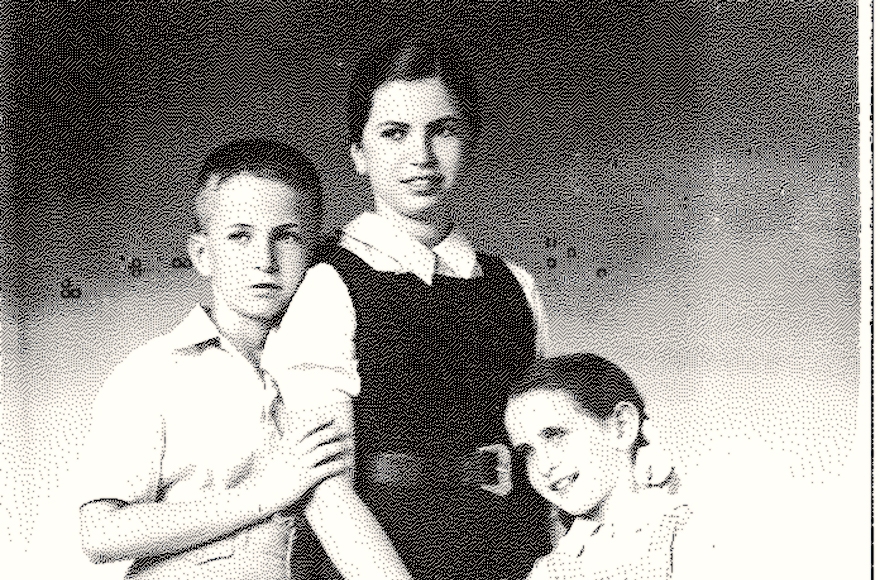

Aranka Rosenfeld, center, in May 1933. (Courtesy of Jelena Blumenberg)

The “Seeking Kin” column aims to help reunite long-lost relatives and friends.

(JTA) – When Brazil native Fabio Rosenfeld brought up launching a search for his grandfather’s sister who had survived the Holocaust, I opened my “National Geographic Atlas of the World” to locate her hometown of Reghin.

A week later, the surname and the area struck me as familiar, so back to the atlas I went. There was Reghin, in the Transylvania region of Romania and Hungary, near Cluj-Napoca, a town central to a “Seeking Kin” column about an old Hungarian-Jewish cookbook whose author was given as Mrs. Martin Rosenfeld.

A month after that second atlas encounter, Fabio Rosenfeld emailed information he had just gleaned while searching for his great-aunt, Aranka Rosenfeld. Alas, it wasn’t about her.

Instead, it dealt with the cookbook’s author possessing the same name. A mention of that Aranka Rosenfeld in a cookbook by the eminent culinary authority Joan Nathan included a comment from Rosenfeld’s granddaughter, Jelena Blumenberg.

An online search located Blumenberg living in Manhattan. She was thrilled to be found and learn about Tara Lotstein, the Washington, D.C., woman who had bought Blumenberg’s grandmother’s work, “A Jewish Woman’s Cookbook.” The purchase launched Lotstein’s search for several people, including its author.

“I was very touched and so surprised that her cookbook is [still] read and used. I’m so happy,” Blumenberg said.

Blumenberg, 68, filled in key information about her grandmother, who was born in Halmay, Hungary, in 1898, and lived mostly in Szikszo and Subotica until passing away in March 1981.

“Aranka saw all her children die in her life,” Blumenberg said. “She had a very tragic life, really. She was a lovely, amazingly sweet person.”

Rosenfeld’s parents, Adolf Span and Laura Engel, were observant Jews who owned a mill in Szikszo. One of seven children (all but one of them girls), Aranka married Martin and they settled in Subotica, where they owned a large hardware store and lived upstairs. Circa 1938, the Rosenfelds moved to Belgrade, Serbia, to open a factory manufacturing stoves. They returned to Subotica and during the Holocaust were incarcerated in its ghetto.

Martin was murdered in Auschwitz, along with approximately 80 members of Aranka’s family. The Rosenfelds’ son, Imre, was killed by the Germans in 1944 while fighting for a resistance movement. Aranka and daughters Eva and Vera were incarcerated at a labor camp in Austria and survived the Holocaust. Vera married at age 16, and in about 1948 she and her husband, Pista Pernicer, moved to Israel and Hebraicized their surname to Orr. They lived in Tiberias and Haifa and had three children: Reuven, Gavriel and Daniella. Vera died of breast cancer in her early 40s; her husband passed recently.

Postwar, Blumenberg’s mother, Eva, became a journalist, married a Jewish communist named Zoltan Biro and worked in Belgrade, where Blumenberg and sister Judith were raised. Rosenfeld returned to Subotica, by then nearly devoid of its once-thriving Jewish community. Their ornate synagogue couldn’t always draw 10 men for public prayers, but Rosenfeld – “she came to services every Friday night,” Blumenberg recalled – would be counted in the minyan (quorum).

All the while, she cooked. Blumenberg visited regularly, with Subotica and Belgrade just over 100 miles apart.

“I remember very well her fried chicken, which was exquisite. She had her secrets [for that dish], and would fry the parsley. She cooked stuffed cabbage, goulash and palachinta, which are crepes or blintzes,” Blumenberg said.

Blumenberg said Rosenfeld taught the sisters how to cook.

“We hung around her all the time when she was cooking,” Blumenberg said. “She gave cooking classes in Subotica occasionally for young women – not Jewish women; there weren’t any.”

That’s cruelly ironic, given the cookbook’s stated audience. Blumenberg has two of her grandmother’s original hard-covered cookbooks, published in the late 1930s: one beige, one red. Judith, who still lives in Belgrade, also owns two. The books survived the Holocaust because a neighbor safeguarded some of the Rosenfelds’ possessions, including photograph albums.

In fact, a Budapest publishing company reprinted the cookbook a decade ago, although it removed Rosenfeld’s name as author. Blumenberg said she hasn’t demanded that her grandmother receive credit. Rosenfeld, she added, also published two small Hungarian-language cookbooks in Israel, presumably while visiting her daughter in the country’s early years.

The mention of Aranka Rosenfeld that would help “Seeking Kin” connect Blumenberg and Lotstein was contained in “Joan Nathan’s Jewish Holiday Cookbook.”

“I’m thrilled,” Nathan said of her book’s role. “Some people look at their recipes and wish they had something of their past. Think of whole towns filled with recipes, whole generations killed in the Holocaust. When you find these threads – I’m just excited by that.”

Fabio Rosenfeld said he, too, is happy about the search he unwittingly helped solve.

“It must be part of the 613 mitzvot, a kind of tzedakah without money,” he said. “The real tzedakah is when you give something to someone you don’t know.”

(Please email Hillel Kuttler at [email protected] if you would like “Seeking Kin” to write about your search for long-lost relatives and friends. Please include the principal facts and your contact information in a brief email. “Seeking Kin” is sponsored by Bryna Shuchat and Joshua Landes and family in loving memory of their mother and grandmother, Miriam Shuchat, a lifelong uniter of the Jewish people.)

This entry passed through the Full-Text RSS service – if this is your content and you’re reading it on someone else’s site, please read the FAQ at fivefilters.org/content-only/faq.php#publishers.