Why are Bob Dylan’s archives in Tulsa?

The reasons the Bard chose Oklahoma as the home for his collection may have more to do with politics than money

Bob Dylan.

This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Published May 3, 2022

Why Tulsa?

To be more precise: Why is the new Bob Dylan Center – home to the Nobel Prize laureate’s archive as well as gallery space that will perpetually play host to 16 revolving exhibitions based on the archive’s holdings — located in Tulsa, Oklahoma, of all places?

As it turns out, there are many reasons. The city of 400,000 is already home to the Woody Guthrie Center, where the archives of the venerable 20th century folk singer (and Oklahoma native) who was a huge influence on Bob Dylan – one of whose very first original compositions was entitled “Song to Woody” — are housed. When it came time to negotiate with Bob Dylan to entrust his archives, including memorabilia, notebooks, recordings and films, to a team of civic and academic suitors, Tulsa had a huge leg up on the competition, playing on Dylan’s emotional attachment to Guthrie as well as demonstrating the thought and care that has been put into representing and preserving Guthrie’s legacy in a manner befitting the folk bard of America.

Or, just look at a map. Tulsa is smack dab in the center of the United States. Anyone looking for symbolism in where Bob Dylan’s legacy will be made available to generations of visitors and scholars will not overlook the fact that it is in the heartland of America, just where one might expect to find what will undoubtedly become ground zero of Dylan studies. Perhaps the greener pastures of Harvard University may have been more befitting a Nobel laureate. Maybe an NYU-based museum in Greenwich Village, New York, where Dylan quickly made his mark on the burgeoning early-1960s folk scene on his way to rock ‘n’ roll superstardom by the mid-1960s, would have made instant sense – as well as having the advantage of being located in a major media market with a built-in tourism infrastructure.

Even Minneapolis may have been a more logical location, a nod to Dylan’s home state of Minnesota (he was born in Duluth and grew up in the iron-mining town of Hibbing near the Canadian border) and the city in which the teenage Robert Allen Zimmerman first began performing in folk clubs while attending (or, more precisely, not attending) university, and where he first adopted the stage name by which the world has always known him (and which he made his legal name in August 1962).

No doubt the benevolence of Tulsa’s best-known billionaire – the civic-minded George Kaiser – whose eponymous Family Foundation has transformed the city’s early education efforts as well as its landscape, having underwritten a Central Park-style stretch of public garden called the Gathering Place — a 66-acre park believed to be the largest public park in the country built with private funds – went a significant way toward winning the Dylan archive for Tulsa.

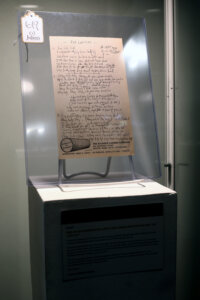

According to Forbes magazine, Kaiser is worth over $10 billion, placing him in the top 200 of richest people on earth, and one of the top 25 most philanthropic billionaires in the United States. The check he reportedly wrote for $20 million to bring the archive to Tulsa must have been enticing, even if it was a virtual steal: an original, handwritten sheet of lyrics for the song “Like a Rolling Stone” alone fetched $2 million at auction in 2014. There are approximately 100,000 items in the archive, and while they are not all lyrics to groundbreaking songs, the math is simple: if it were just a question of dollars and cents, the Dylan collection could have been auctioned off piecemeal for at least 10 times as much – maybe more — as Kaiser paid for the whole shebang.

Kaiser, who was born and raised in Tulsa by Holocaust refugee parents, once admitted to The New York Times that he was never a huge Bob Dylan fan, but more of an appreciator of his accomplishments in the pantheon of American music. The Harvard graduate’s musical taste tended more toward one of Dylan’s earliest champions. “I was taken by Joan Baez in college,” Kaiser told the Times, “when she was singing down the block,” presumably referring to the famed Club 47 in Cambridge’s Harvard Square where Baez frequently performed.

Like most fortunes made in Tulsa, Kaiser’s was built on oil in this one-time capital of the U.S. oil industry. Kaiser took over his family’s Kaiser-Francis Oil Company in 1969, and when the Bank of Oklahoma was teetering toward failure in 1991, he scooped it up for a mere $60 million. Fortunately for Tulsa, Kaiser has proven to be a benevolent municipal oligarch; he was a charter signee of the Giving Pledge, the challenge issued by founders Bill Gates and Warren Buffett to billionaires to commit to giving away more than half their wealth to charitable causes. Forbes named Kaiser to their list of Top 25 Most Philanthropic Billionaires in 2021. The George Kaiser Family Foundation has already paid out more than $1.3 billion, a significant amount of which has remained in Tulsa.

About the foundation’s devotion to early childhood education efforts, Kaiser famously once said, “Those who have won the ovarian lottery by being born in an advanced society to loving parents have a special obligation to help restore the American Dream.” Kaiser has also been a generous donor to Jewish organizations and programs in Tulsa. His family history is never far from the surface. His mission statement includes this phrase: “My family joins me in my intention to … focus these efforts in the community that welcomed my family from Nazi Germany.” Kaiser is also a major donor to Democratic candidates and was a “campaign bundler” for Barack Obama. According to The New York Times, Kaiser likes to refer to himself as a “robber baron from red-state America” who has come to love public preschool. (George Kaiser trivia: his nephew is actor Tim Blake Nelson.)

Jews first settled in Tulsa around the turn of the 20th century. The original coterie, who arrived in 1902, were mostly from Latvia. As in countless towns throughout the U.S., the early immigrants set up shop as merchants, selling clothes, groceries, and home goods to those working in the nearby oil fields (a situation not unlike that of Dylan’s forebears, who likewise set up shop in downtown Hibbing and supplied appliances and home goods to that town’s iron miners).

A few Jewish immigrants found their way into the oil business and helped create a small but thriving Jewish community in Tulsa: Emanuel Synagogue, a Conservative congregation, was founded in 1904; a mutual aid bank and a Hebrew Free Loan Society were established; Temple Israel was founded in 1914 as a Reform synagogue; and Congregation B’nai Emunah was founded in 1916 as an Orthodox synagogue. The state was not unfriendly to Jews: its first Secretary of State, Leo Meyer, served from 1907 to 1911. Today, of course, there is even a Chabad house in Tulsa, which is also home to the private University of Tulsa, which serves close to 4,000 students.

While access to the archive will be limited to those doing scholarly research, the 29,000-square-foot center, which opens to the public Tuesday, May 10, includes a 55-seat screening room, where master prints of all Dylan’s films will presumably be shown on a regular basis, including such rarely seen Dylan-directed movies as “Eat the Document” and “Renaldo and Clara.” There are also reportedly film and audio recordings of virtually every Bob Dylan concert from the past 60 years. The master tapes of all Dylan recordings will be housed there, and one public exhibition will be set up to allow visitors to remix songs including “Like a Rolling Stone” and “Chimes of Freedom.” Who knows: maybe “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” (aka “Everybody Must Get Stoned”) might sound better with more cowbell?

Curiously, in the more than 600 songs that Dylan has written, it wasn’t until 2020 that he referred to Tulsa. In the 17-minute epic, “Murder Most Foul,” that concluded his album “Rough and Rowdy Ways,” Dylan sang, “‘Take Me Back to Tulsa’ to the scene of the crime.” “Take Me Back to Tulsa” was the name of a hit song by Bob Wills, who is widely considered the founder of Western swing. Wills first recorded and released the song just a few months before Dylan was born. He even performed it at Cain’s Ballroom, the historic Tulsa music venue that exists to this day and that is playing host to three concerts celebrating the opening weekend of the Dylan Center by artists inextricably linked to Dylan himself: Mavis Staples, Patti Smith and Elvis Costello.

The second half of that phrase, “to the scene of the crime,” presumably refers to one of the darkest episodes in American history: the so-called Black Wall Street massacre of 1921, a veritable pogrom in the predominantly Black Greenwood District of Tulsa. Dozens were killed and hundreds were injured as the authorities aided and abetted the destruction by fire of more than 35 square blocks of the neighborhood — at the time one of the wealthiest Black communities in the United States — rendering more than 10,000 people homeless. For nearly 100 years the history of the massacre was not taught in Oklahoma schools; it was only in 2020 that it officially became part of the Oklahoma school curriculum.

With his lifelong devotion to the cause of civil rights in song, from “Blowin’ in the Wind” through “Murder Most Foul,” perhaps Bob Dylan also felt that locating his archive in Tulsa was one small, symbolic step toward shining a light from the west down to the east on America’s original and enduring sin.