Where to see six priceless sketches by renowned artist David Friedmann in St. Louis

David Friedmann in 1936 in his apartment at Paderborner Strasse 9, Berlin-Wilmersdorf. In the background his painting of the Berlin Cathedral appears. After World War II, it was found in his sister-in-law’s apartment. Friedmann’s painting of the Schlossbrücke und Zeughaus (castle bridge and arsenal), today the German Historical Museum, also appears. These paintings are among hundreds of Nazi-looted and lost artworks.

Published July 11, 2022

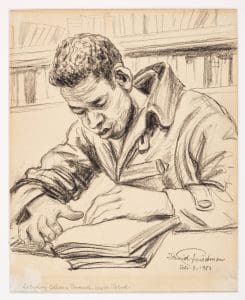

A nun of unknown order sits quietly at a table under the roof of the public library. She writes diligently in her journal, surrounded by stacks of books, unaware that she is being anonymously immortalized by a roving pen. For several long, unbroken minutes, she remains in her seat, unmoving but for the scrawling of her own pen and the turn of a page. Then, at last, she lets out a breath and begins to pack up. What is left is an unobtrusive sketch now complete by the hand of a man tucked quietly behind a bookshelf.

This man is David Friedmann.

On a chilly day in April, I was called to the Great Hall in downtown Central Library to assist in setting up an exhibit of some of the library’s more unique or quirky holdings. We spent over an hour arranging vintage pictures of strangers reading or posing with books dating from the 1920s and 30s, displaying assorted ephemera left in library books by patrons, and meticulously straightening and re-straightening six candid pencil sketches. The sketches were obviously from the hand of a talented artist, but they seemed like such innocuous pieces of art: a man reading a newspaper with his foot propped up on his knee, an elderly gentleman nodding off over his book, a nun studiously writing in her journal. They were all such normal depictions of everyday life.

Little did I know the saga of hardship, resilience, and passion that hid behind each pencil stroke…

David Friedmann was born to a Jewish family in 1893 in Mährisch Ostrau, a city in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Even as a child, he showed remarkable interest and skill in art, which led him to emigrate to Berlin in 1911 to study painting under the prominent artist Lovis Corinth and etching under Herman Struck. However, his burgeoning career was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I, during which he served as an officer in the Austro-Hungarian army. After the war was over, he returned to his work in Berlin. While in Berlin, his reputation as a talented artist grew exponentially. Throughout the 1920s, he produced candid sketches of champion chess players and portraits of prominent personalities for the newspapers, including Albert Einstein, Max Liebermann, and Thomas Mann. In 1925, he even created a lasting tribute to his mentor by immortalizing the final day of Corinth’s public wake.

David Friedmann was born to a Jewish family in 1893 in Mährisch Ostrau, a city in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Even as a child, he showed remarkable interest and skill in art, which led him to emigrate to Berlin in 1911 to study painting under the prominent artist Lovis Corinth and etching under Herman Struck. However, his burgeoning career was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I, during which he served as an officer in the Austro-Hungarian army. After the war was over, he returned to his work in Berlin. While in Berlin, his reputation as a talented artist grew exponentially. Throughout the 1920s, he produced candid sketches of champion chess players and portraits of prominent personalities for the newspapers, including Albert Einstein, Max Liebermann, and Thomas Mann. In 1925, he even created a lasting tribute to his mentor by immortalizing the final day of Corinth’s public wake.

The 1930s, however, would begin a decades-long trajectory of loss and terror as Friedmann was forced to flee his chosen home in Berlin for the city of Prague, leaving behind his life’s work to be looted by the Nazis. From 1938 to 1941, Friedmann, his wife Mathilde, and their young daughter Mirjam Helene resided in Prague where Friedmann supported his family with his art skills before being sent to the Łódź Ghetto, once again leaving behind his work to be looted by the Nazis. While living as a refugee in Prague and later as a prisoner in the ghetto, Friedmann’s art captured moments of both joy and despair as well as snapshots of daily life in the ghetto and has served as a means of identifying survivors and victims alike in the years since their creation.

The family’s imprisonment in the ghetto ended with their deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. Friedmann was then transported to the Auschwitz subcamp Gleiwitz I, where he managed to survive by scrounging together art supplies out of camp detritus and impressing the SS officers stationed at the camp with his work.

Friedmann’s wife and daughter did not survive. In 1945, David Friedmann was liberated from Blechhammer by the Soviet Army. He was 51 years old, the only member of his family to survive, and faced with the prospect of starting his life over from scratch. But he was not cowed.

Over the next few years, he met and fell in love with another survivor of the concentration camps, a woman named Hildegard Taussig, whom he married in 1948. The following year, they fled communist Czechoslovakia for Israel, where they had their first and only child, also named Miriam, the year after that. Throughout the early 1950s, Friedmann helped to jumpstart the industrial art scene in the newborn country, but when the opportunity to immigrate to America came in 1954, Friedmann seized it with both hands and became a prominent commercial artist here in St. Louis.

ADVERTISEMENT

By 1962, Friedmann was retired from his career, but the memories of his time in the ghettos and camps haunted him still. Since his liberation, Friedmann had produced a constant stream of artwork depicting his time under the Nazi bootheel, culminating in his series “Because They Were Jews!” which served as a visual diary of his time in Łódź and Auschwitz. The pain of recreating these memories through art led Friedmann to seek respite in local parks and libraries, sketching everyday scenes of everyday people doing everyday activities. Doing so was a way of reconnecting with his love of art outside of the pall cast by his more serious subjects. In January of 1963, Friedmann’s therapeutic ventures led him to Central Library where he began anonymously sketching a series of strangers from the secrecy of the bookshelves.

Upon his passage in 1980, a handful of these sketches were gifted to St. Louis Public Library through the generosity of his wife and daughter. The subtle power of those images stood out to me even after nearly sixty years, prompting an interview between myself and Friedmann’s own daughter, Miriam Morris.

Although she now lives in New York, Miriam was kind enough to spend nearly two hours with me talking via Zoom about the remarkable life of her father. Throughout our discussion, I was struck by Miriam’s tireless drive to see her father’s work realized and celebrated as it deserves. She shared stories of his triumphs and his challenges, constantly centering his life and experiences in a way that spoke of boundless love and devotion that was clearly reciprocated between her and her parents. For all his accomplishments and achievements, David Friedmann saw the sun in his daughter’s eyes. It is that love, for his family, for his people, for his art, that lives beyond him now. We, here at St. Louis Public Library, are lucky enough to have six priceless examples of this love for the common and everyday musings of common and everyday people by a man who was anything but.

I close this blog now with a profuse thank you to Miriam Friedman Morris for sharing her time and her story with me. I am enormously honored and touched by her generosity and her dedication to her father’s memory. On a more personal note, I find that I am moved to explore the preservation of my own family’s story. My parents’ generation is the old guard now, having lost my last grandparent in November of last year. If these memories and moments are to live beyond them though, it falls to us to carry the torch into tomorrow by recording and preserving the stories they left behind in their art, their work, and their homes.

Visit Central Library’s Great Hall to see these sketches from “Enjoyment in Libraries with the Candid Pencil of David Friedman(n) (1893-1980)” and selections from the Gregory P. Ames Photograph Collection, A Celebration of Readers and Reading.