The greatest Jewish Hollywood character you’ve never heard about

Published September 8, 2022

You hear the name Duke in Hollywood and you picture a mountain of a man in a weathered Stetson firing his Colt from a speedy horse. Well, this isn’t about him. It’s about another Hollywood Duke — a short Jew in a fedora firing expletives from his mouth. The smoking weapon in his hand was a cheap cigar.

In the mid-1970s, in New York, my writing partner and I worked on a sitcom produced by comedian Alan King. Alan was a hell of a storyteller, onstage and off. Story conferences would sometimes morph into hilarious anecdotes from burlesque, the Catskills, Hollywood. The subject of a few tales was Maurice Duke.

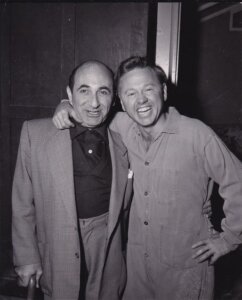

Maurice Duke was a talent manager and film producer. Some tagged him “King of the Bs.” Though to call his films “B-movies” would be overpraising them. By a lot. Duke’s low-rent productions exploited current fads. When 1940s magazines discovered “teenagers,” he launched “The Teen Agers” series. When Top Ten radio arrived, so did his picture, “Disc Jockey.” The Cold War spawned his Mickey Rooney flick, “The Atomic Kid.” And the Twist dance craze of the 1960s gave us “Twist All Night.”

“I made 103 pictures,” he said with a foxy grin, “All of them s—t.”

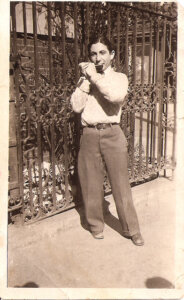

Maurice Duschinsky was one of seven born to Hungarian Jewish immigrants Armin and Melani (Weiss) Duschinsky. He was born — he might’ve called it his release date — on Oct. 27, 1910 in Coney Island, New York. It wasn’t a strong opening. At 10 months of age, he was stricken with polio. “Before it was popular,” he would say.

Polio shaped Duke’s view of life. After that, no misfortune or defeat could be worse than what he’d already faced. It gave him the perspective and resilience to thumb his nose at any setback and say, “Next!” That became his mantra: It’s over. Next!

ADVERTISEMENT

Duke walked with the aid of a brace and cane. His metal brace was hinged at the knee. To walk, he’d lock the joint so the knee couldn’t bend, then step forward with the good leg, swing the braced leg, and use the cane to stay upright. You didn’t want to distract him. “I can’t stop once I’m in motion!” Sometimes if there was a line at the deli, he’d say, “Make way, wounded veteran!”

“My friend Duke,” the pre-Don Rickles insult comic Jack E. Leonard once said by way of introducing him, “the only guy who walks around with his own Erector set.”

Duke learned to play harmonica in a bed at Children’s Hospital. He won a contest and formed the Cappy Barra Harmonica Band, a vaudeville troupe, becoming their manager at 21. Eventually, he’d go on to manage the careers of Mickey Rooney, Zero Mostel, actor Mike Connors, broadcaster Tom Snyder, and the dog Lassie. But in 1931 his only other client was friend and meshuggener Henry Nemo (Nuni Bregman). Nemo, who would later write such hit tunes as “’Tis Autumn,” and “I Let a Song Go Out of My Heart,” would do anything for a laugh, so Duke booked him into Borscht Belt hotels as social director or tummler.

“Nemo and I were driving to California,” Duke once said. “I tell him the fresh air is doing wonders for my health. So, every day, when I’m napping, the Neem shaves a little off the bottom of my cane, then replaces the rubber tip. When we get to LA, I stand and say, ‘Neem, this climate’s great, I’ve grown 2 inches!’”

“Once, he insisted we stop at the Museum of Science and Industry. He wants to show me the largest magnet in the world. It’s the size of a house. So, we get there and he keeps pushing me closer and closer to the magnet. Finally, the magnet pulls my metal brace, and I’m hanging upside down.”

The man could talk. He’d jab the air with a lit cigar and he’d get a lot into a sentence by keeping most words to four letters. At 40, he convinced a stunning 20-year-old Texas model named Evelyn Williams to marry him. The marriage was good, the divorce better. In 1983, their kids hosted a star-studded Hollywood roast for the 25th anniversary of their split.

In 1991, I had a first lunch date with the woman I would take a second shot at marriage with. When I asked Fredde about her parents, she said, “You probably never heard of my dad. He’s a producer named Maurice Duke.”

“The one Alan King talked about? With the brace and the cane?”

She was shocked I’d heard of him. I was shocked he was alive.

On our next date she said, “How would you like to meet my dad?”

“Sure,” I said, unaware he was in Brotman Hospital recovering from a stroke. But this was not your father’s stroke patient. He was taking calls, holding court, ordering the nurse around.

Months later, she asked her father what he thought of me. “Nice guy,” he said, “but he’ll never marry you.” Duke wasn’t always right about stuff. In Germany, in 1961, he turned down an offer to manage some group called the Beatles.

But back to ‘51.

Martin & Lewis were the hottest guys in show business, banging out hit movies for Paramount. Duke had an epiphany: “Why should Martin & Lewis be the only ones allowed to make Martin & Lewis pictures?” So, he found a skinny kid, a carbon copy of Jerry Lewis named Sammy Petrillo, teamed him with an Italian crooner and hired Bela Lugosi for, er, name value: Lights! Action! Lawsuit!

Jerry Lewis and Paramount got wind of Duke’s low-budget knockoff and sued him for theft of intellectual property. (If you’ve seen Martin & Lewis’ act, “intellectual” may not be the word that comes to mind.) Soon, there was talk of a settlement; Paramount would pay Duke to bury his movie. Duke stood to make more by burning the negative than releasing the film. He thought it over for oh, maybe two seconds.

But first, Paramount wanted to see the picture. Duke refused and decamped to Palm Springs. That’s when disaster struck. His producing partner, Jack Broder, agreed to screen “Brooklyn Gorilla” for Lewis and Paramount.

When the lights came up in the screening room, they knew this cheapo production was no threat. The deal was dead.

Duke was crushed. So close. Woulda been the score of a lifetime. What a heartbreaker.

“Next!”