Leonard Bernstein at 100: 7 treasures from the Library of Congress’ celebration of the Jewish maestro

Published April 16, 2018

The American-born son of Ukrainian Jewish immigrants, Bernstein’s influence spanned the musical world, from classical music to Broadway.

Thousands of events are featured as a part of #Bernsteinat100, including “Leonard Bernstein: The Power of Music,” an exhibit that recently opened at the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia.

Last week, the Library of Congress got in on the act, making available online for the first time free access to more than 3,700 items including letters, photographs, audio recordings, and other material from its vast Leonard Bernstein Collection. The release nearly tripled the library’s digital offerings.

Curious fans with time on their hands can cue up “West Side Story,” “On the Town” or the “Chichester Psalms,” and peruse volumes of scrapbooks in the Library’s collection that were meticulously compiled by Helen Coates, his piano teacher and later, his career-long secretary.

“Bernstein arguably was the most prominent music figure in America in the second half of the 20th century,” according to Mark Horowitz, the collection’s curator, who has been immersed in the details of the maestro’s life for a quarter century. He described Bernstein as a “polymath, a Renaissance man who wanted to do it all,” from music to education to social activism.

Born on Aug. 28, 1918 in Lawrence, Massachusetts to Jennie and Samuel Bernstein, the young musician famously catapulted onto the world stage in November, 1943, when he filled in on short notice as conductor for the New York Philharmonic for an ailing Bruno Walter, in a concert broadcast on national television.

Five years later, with his 1958 appointment as music director of the New York Philharmonic, Bernstein became the first American-born and educated conductor — and the first American Jewish conductor — to lead a major American orchestra.

With an estimated 400,000 items, the Bernstein Collection is one of the largest and most varied in the Library’s music division, Horowitz told JTA. The archives fill 1,723 boxes that measure 710 linear feet.

Here are seven treasures from the Library of Congress collection:

1. Bernstein grew up in Boston in a deeply religious family and was influenced by the music he heard at Congregation Mishkan Tefila.

Leonard Bernstein with his parents, Jennie and Samuel Bernstein, circa 1921. (Library of Congress, Music Division)

At Congregation Mishkan Tefila, his family’s synagogue, the young Bernstein came under the influence of Solomon Braslavsky, a Viennese composer who became the synagogue’s music director and led its choir. On Oct. 10, 1946, Bernstein wrote to Braslavsky, shortly after Yom Kippur: “I have come to realize what a debt I really owe to you … for the marvelous music at Mishkan Tefila services. They surpass any that I have ever heard.”

Bernstein had a strained relationship with his father, a successful business owner, whose life was guided by Talmudic learning. While he described his father as authoritarian, he admired his depth of knowledge of Jewish texts and thought.

2. Bernstein’s Harvard years were instrumental in shaping his music.

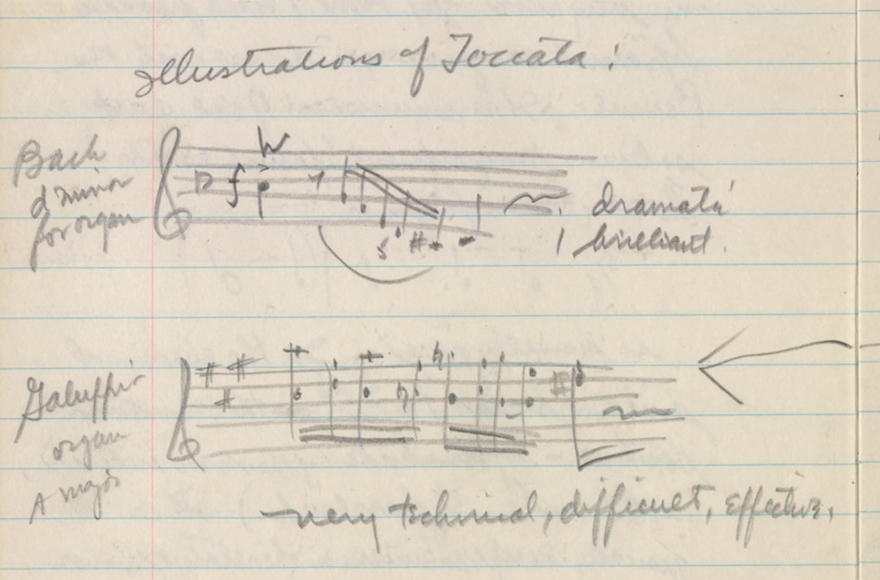

A handwritten page in a notebook from Bernstein’s Harvard days. (Library of Congress, Music Division)

A page in a bluebook dated Jan. 25, 1937, during Bernstein’s sophomore year at Harvard University, displays “handwriting thoroughly familiar to a Bernstein scholar,” according to Carol Oja, a professor at the Harvard Department of Music. In the exam book, Bernstein described Baroque-era toccatas, a musical notation for virtuosic keyboard, as “dramatic, brilliant, … and very technical, difficult, effective.” These descriptions “would later characterize his own compositions,” Oja observed in an email.

3. Bernstein was smitten by Israel and became a devoted and influential supporter of the Israel Philharmonic.

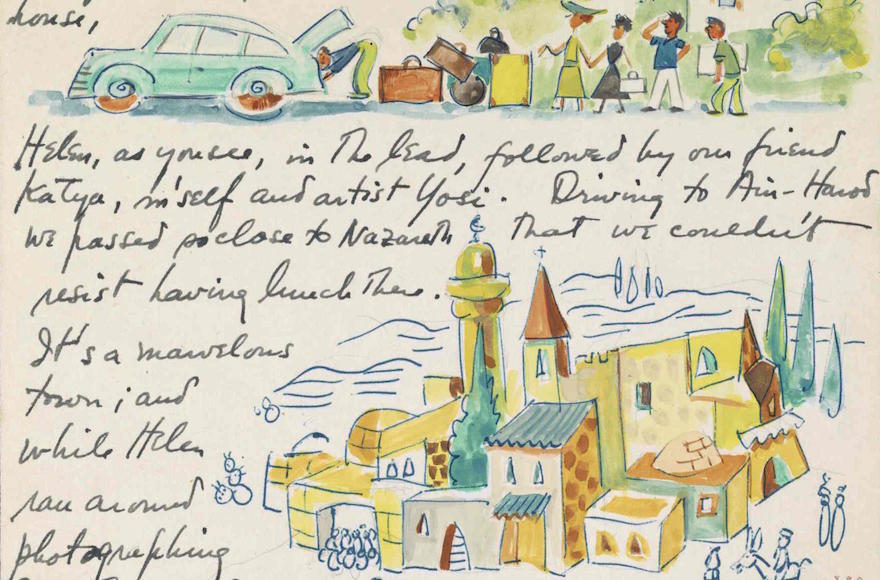

“It’s a marvelous town … I had a glorious Arab meal with khumus and T’hina,” Bernstein wrote about a lunch in Nazareth. This is the first page from a long letter he wrote to his mother, with illustrations by Yossi Stern. (Library of Congress, Music Division)

In November 1948, during Israel’s War of Independence, amidst fighting between the Israeli and Arab armies, Bernstein made his second conducting tour of Israel. He wrote a nine-page letter to his mother, Jennie, that glows with colorful, playful illustrations by Yossi Stern, a Hungarian refugee who became known as the “painter of Jerusalem.”

“You can see his passion for the young state of Israel, its land, the people and the culture,” according to Ivy Weingram, curator of the exhibit at the NMAJH, where visitors can see one page of the original letter, on loan from the Library of Congress.

Over his career, Bernstein conducted the Israel Philharmonic in 25 different seasons, in Israel, Europe and the U.S.

4. Following the Six-Dar War, Bernstein performed a concert in Israel.

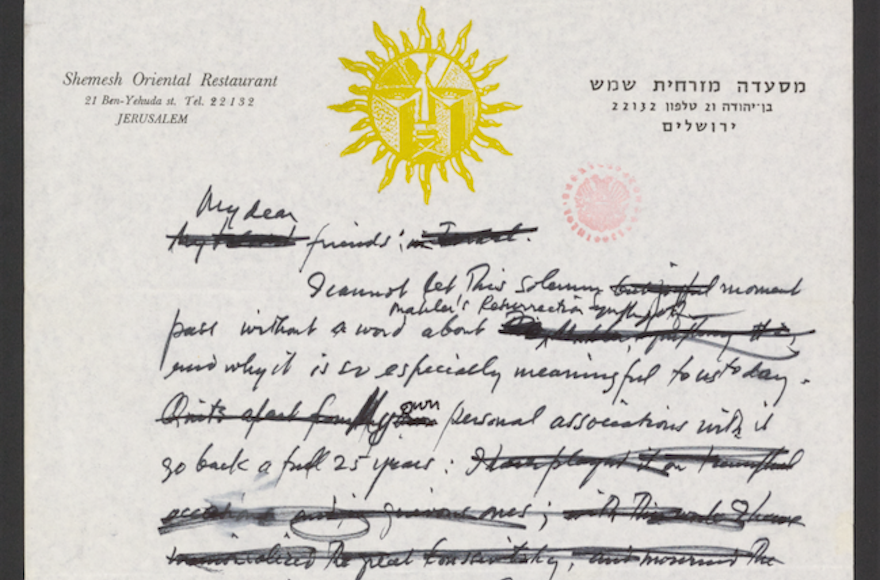

A handwritten speech Bernstein wrote for a concert in Israel, July 1967. (Library of Congress, Music Division)

The July 1967 concert, with violinist Isaac Stern and the Israel Philharmonic, included Hatikvah, Israel’s national anthem; Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto; and the final movement of Mahler’s Second Symphony, known as the “Resurrection Symphony.”

In his speech at the performance, handwritten on stationery from Jerusalem’s Shemesh Oriental Restaurant, Bernstein recalled his exhilaration conducting the Mahler symphony 19 years earlier, during Israel’s War of Independence. He marveled at the recent unification of Jerusalem, a city he envisioned would inspire peace.

“Is it too much to hope that this growing together of people in peace may radiate out to this general region … and eventually …the world,” he wrote. “Why not? This is Jerusalem,” with the name of the city written in Hebrew.

5. Bernstein was gay. His wife Felicia seemed okay with that.

Bernstein and his wife Felicia leaving for Israel in 1957. (Library of Congress, Music Division)

In 1946, Bernstein married Felicia Cohn Montealegre, a Chilean actress who performed the role of narrator in Bernstein’s Symphony No. 3, the “Kaddish Symphony.” They had three children, Jamie, Alexander and Nina.

Bernstein didn’t hide his homosexuality and attraction to men from his wife. Early in their marriage, Felicia wrote a stirring and remarkably broad-minded letter, undated, that revealed the deep love and bond between the couple.

“You are a homosexual and may never change — you don’t admit to the possibility of a double life, but if your peace of mind, your health … depend on a certain sexual pattern, what can you do?” she wrote. “I am willing to accept you as you are, without being a martyr. I happen to love you very much …”

6. “West Side Story” was originally about Jews and Catholics.

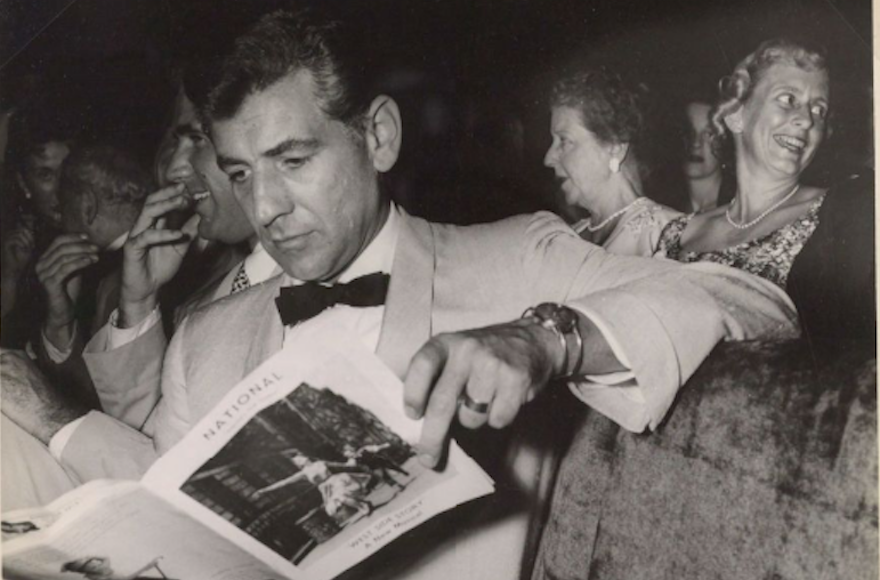

Leonard Bernstein at the opening of “West Side Story” at the National Theater in Washington, D.C., Aug. 12, 1957. (Library of Congress, Music Division)

In the 1950s, Bernstein and choreographer Jerome Robbins took inspiration from William Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet,” adapting it to the ethnic and racial tensions of the 20th century. An annotated copy of “Romeo and Juliet” in the Library of Congress collection is on view at the NMAJH exhibit and includes notes by Bernstein and Robbins. It was originally conceived as “East Side Story,” about conflicts between Jews and Catholics. Audition notes for “West Side Story,” which opened on Broadway in 1957, include Bernstein’s comments about a young Warren Beatty, who sought the role of Riff (“Good voice, can’t open jaw — charming as hell — clean cut”).

7. Bernstein had a passion for education

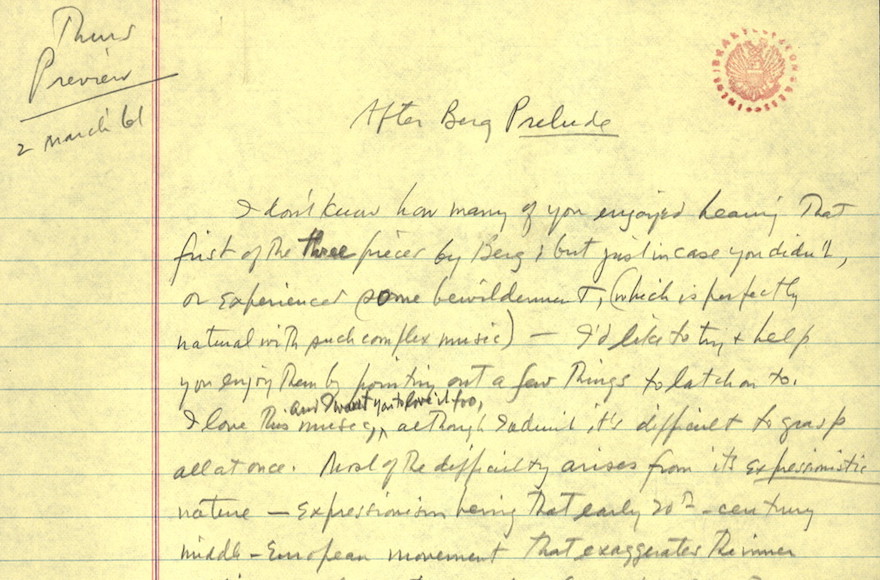

A handwritten page of a lecture for Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts. (Library of Congress, Music Division)

Bernstein relished his role as an educator. His children often say it’s among their father’s most enduring legacies. Just two weeks after beginning his notable role as music director of the New York Philharmonic, Bernstein stepped up to the podium at Carnegie Hall to lead the first of his dozens of Young People’s Concerts. It was the first time the series was broadcast live on national television, bringing the engaging maestro into America’s living rooms.

For the Feb. 28, 1961 Young People’s Concert, Bernstein captivated his audience with the question, ‘What Makes Music Funny?” The 39-year old maestro started off with a joke about an elephant and a mouse. Humor, even in music, needs an element of surprise, he said. “It’s like a bag full of tricks coming at you,” and always has “something new and eye opening.”

Throughout, Bernstein lifted his baton, leading the orchestra in selections from Haydn and Gilbert and Sullivan to Prokofiev and Brahms.

The Library of Congress is hosting a series of programs from May 12-19 including performances and film screenings. On Saturday, May 19, rarely seen materials from the collection will be on display. More details on the Bernstein events are on the Library’s website.