How Pixar’s ‘Soul’ borrows from an ancient Jewish idea

Published December 28, 2020

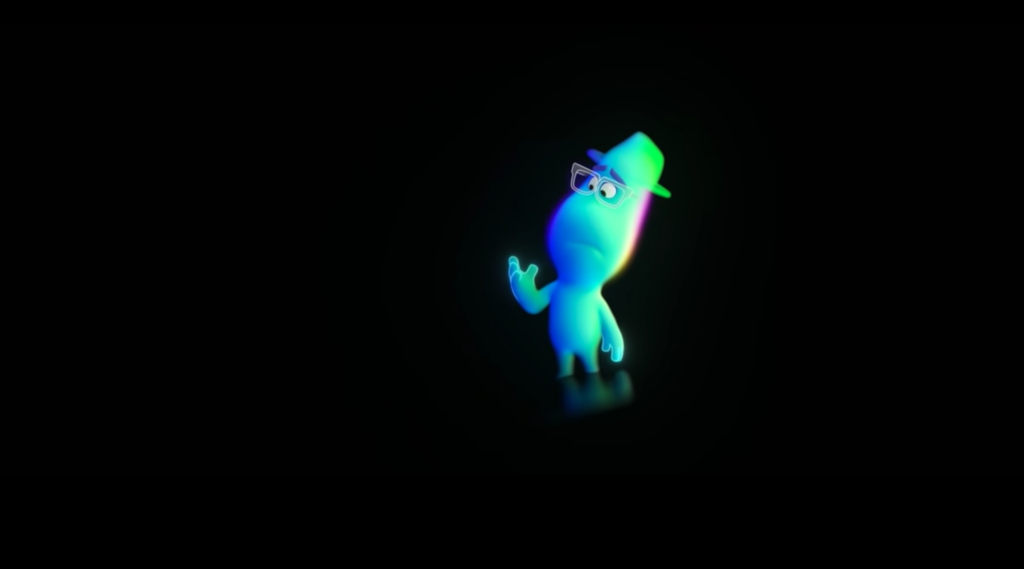

(JTA) — Pixar’s “Soul,” released on Friday on Disney+, is a tender balm of a movie about an aspiring jazz musician who dies on the day he gets his big break. Watching “Soul,” which is set in a richly imagined New York City, as well as in a blissed-out, blue-ish, and minimalist realm of unborn souls, in the final days of 2020 is once elegiac (the riotously crowded New York it depicts sure isn’t there at the moment) and soothing, like applying a poultice to a wound. The New York of our dreams may be in limbo, but there’s still Pixar offering its pastel take on, well, limbo.

“Soul” may not feature the nuanced emotional intelligence of the previous Pixar hit “Inside Out,” which takes place mostly inside the head of an 11-year-old girl, nor the devastating power of the opening minutes of “Up,” but it is the first to make its central subject a question of metaphysics. The question of metaphysics. Namely, what is the body and what is the soul?

For those of us who take Pixar’s metaphysical questions seriously — and as a Jew, a rabbi, the father of young children, and an adult who remembers being wowed by the first “Toy Story” in the theater, I take these questions very seriously indeed — ”Soul” offers a great deal to think about. Watching it over the weekend with our two boys gave us a most welcome opportunity to talk about some big-ticket Jewish questions as well as an occasion to sit back and inhabit a lush world beyond the little realm of our apartment.

ADVERTISEMENT

For a movie about the nature and destiny of the soul, “Soul” is wisely spare when it comes to explicit religious content. Quite simply, there isn’t any. The abstract beings (all named Jerry or, in one case, Terry) that guide souls in the hereafter and in the Great Before are somewhat godlike, but they certainly don’t seem to be gods. And the subject at hand isn’t why things work as they do, or, really, what the capital-M Meaning of it all is. Instead, the story of Jamie Foxx’s poor Joe Gardner is focused squarely on questions surrounding the nature of his soul’s “spark” (and the spark of one other lost soul, voiced by Tina Fey) and what that has to do with his body and his path through life.

“Soul” offers a variety of sweetly packaged, life-affirming answers to these big questions, answers that have resonances in a variety of world religious traditions. Certainly, in the Jewish mystical tradition, there is much ado about soul sparks. There are also cognate visions of the Great Before, my personal favorite being the Kabbalistic image of the tree of souls, hung richly with the fruit of future lives, which, when ripe, are blown down to earth by a light wind. This particular image doesn’t appear in Pixar’s version of things, but it is certainly of a piece with the gentle realm where new souls are nurtured before birth.

It doesn’t give too much away to tell you that one of the movie’s central messages is that true personhood is rooted in the union of body and soul, that they are both indispensable ingredients of life’s confection. If Joe Gardner’s adventure with an unborn soul named “22” yields any concrete moral, it is that corporeality and spirituality are intimately bound up with one another. Each is incomplete, perhaps woefully so, without the other. And of the many ideas that Pixar gracefully bandies about in “Soul,” it is this one that strikes me as the most profoundly Jewish.

ADVERTISEMENT

On this very subject, there is a famous midrash, or ancient rabbinic homily, about a body and soul separated by death and standing before God in judgment. The soul, pleading her case, argues that all of her sinful behaviour was caused by the body’s base desires. The body, not to be outdone, makes the point that without the soul he would have been entirely lifeless and therefore unable to transgress. Accepting their arguments, God puts them back together and punishes them in unison.

I have always found this story irresistibly charming (very much like a Pixar movie) not because I am in love with the idea of divine retribution, but rather because, as an embodied soul myself — or, if you like, as a body who happens to be ensouled for the moment — it simply rings true. One of the enduring contributions of the ancient rabbis is their forceful insistence that we are Jews not only because we have Jewish souls (though they did believe that) but also because we have Jewish bodies, the product of Jewish families and pumping with Jewish blood. The human being, in this view, is not a metaphysical construct — as Tina Fey’s character somewhat derisively describes the realm of souls. Nor is the human being only a soft, perishable body. Rather, a human being is a luminous, fragile and ultimately temporary marriage of the two. In “Soul,” it is only when our heroes discover and inhabit this truth that they both get to where they need to go.

In a year in which so many bodies have been ravaged — and in which so many souls have been frayed — you can do a lot worse than sitting back and, for just under two hours, allowing Pixar to offer up some humane and very Jewish answers to some very deep questions. The movie itself is perhaps somewhat slight, given it’s rather weighty subject matter, and the answers it gives may not knock your socks off. But they just might soothe your soul, and, as we close the book on 2020, I say that’s plenty. I give it three out of four sparks.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of JTA or its parent company, 70 Faces Media.